Bucket Listing Mt. Mera

Urgent Notice: The situation in Pakistan is beyond urgent. Those of us who have the means to work on our bucket lists ought to see what we can do help out. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has announced that Americans may text the word "SWAT" to the number 50555 in order to donate $10 (per message) to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, who is providing tents, clothing, food, clean water and medicine to Pakistan.

I've been thinking about bucket lists. [If you haven't seen the movie by that name, a Bucket List is a list of things you want to do before you kick the bucket.] Not that I'm about to kick the bucket myself, but it seems like my age cohort is all talking about retirement. Personally, I don't have a career I could retire from. My high school buddy Mark Rosenthal, on the other hand, is now emeritus at SUNY, and has been junketing the world. A week or so ago he came back from Baffin Island with a ton of great walrus shots. Before that, there was the Serengeti. Next up, Antarctica.

I pointed out to him, when we spoke just before his 60th birthday, that the main event on Carter Chambers' list was Mt. Everest. Carter Chambers is Morgan Freeman's character in Bucket List. Mark has never been to Nepal, and it's not even on his list. We have to change that.

SummitClimb leader on Everest (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Carter's approach to Everest is curiously oblique. For one thing, he never refers to it by name. He mentions the Himalayas and "my mountain," but on his bucket list he writes Witness Something Truly Majestic. Apparently, he just wants to see the thing, but when he gets close -- presumably Tengboche monastery -- he finds that he can't see it and he can't do a fly-over because of a storm on the mountain. That's the "shitty news" Carter shares with Edward Cole (Jack Nicholson). Carter's "really shitty news" is that the weather won't clear till spring.

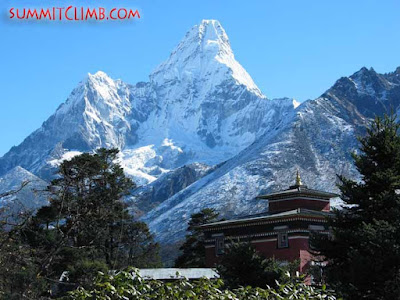

Like most Hollywood screenwriters, Bucket List's Justin Zackham is curiously insouciant as to Himalayan geography, and obviously assumes that the film's viewers are equally ignorant. In the film Passage to India, for instance, David Lean uses a clip of Nepal's Khumbu to represent Kashmir (almost a thousand miles away), even including a full-frame shot of Ama Dablam, a peak as distinctive and nearly as well-known as the Matterhorn. But back to Everest, and Carter's bogus shitty news. For those of our readers who might want to do a fly-over of majestic Mt. Everest, or nearby Ama Dablam (a much more beautiful mountain): the flights originate out of Kathmandu (not Tengboche), and, because of the dry monsoon blowing out of Inner Asia, the winter weather is generally fine. By the way, the Everest fly-over from Kathmandu is $160 for the one-hour round trip; book in advance, and ask for the first flight of the day.

Summit, Ama Dablam (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Okay, that bit about the weather being bad till spring is just a minor inaccuracy. The really weird bit in the movie is that shortly after being diagnosed with lung cancer the Nicholson character climbs Mt. Everest with Morgan's ashes (appropriately, in a Chock-full-o'-Nuts canister like the one Carter had used as an ashtray), and deposits them in a sort of chorten. We don't actually see Edward climb Mt. Everest, but it is strongly implied that Edward did so in order to help Carter polish off his bucket list -- and, thereby, to take care of Help [an erstwhile] Complete Stranger for the Good on his own list.

Not that a geezer can't possibly do Everest -- in fact, the current record-holder, Min Bahadur Sherchan, collected his numerological trophy at 76. And not that Edward doesn't have gumption: after all, he knocks off Goal #7, which is a week in the Louvre. Having barely survived that very ordeal as an eight-year-old, short-leashed by my parents, I have a lot of respect for two geezers who undertake it voluntarily. But unless Edward also undertakes a serious training program, including a number of easier climbs, somebody who looks like Jack Nicholson looked in 2008 (when he made the movie) would not be a contender to summit Mt. Everest. Edward's valet, who parks Edward's ashes in a matching Chock-full-o'-Nuts can next to Carter's, might be a better candidate; still, it's weird that the movie shows him just cruising up a broad gentle snow field to the summit, alone, no ropes, panting a bit but not in any obvious discomfort.

Unfortunately for bucket-listers, Everest is no such piece of cake.

It is also rather exclusive. Climbing fees are extremely expensive ($10,000 per person from the Nepali side, not to mention big bucks for use of the fixed gear at the Ice Fall, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera), and the bureaucratic rigamarole is daunting. In short, the do-it-yourself option outlined for Tashi Laptsa would not be feasible, and even world-class climbers generally have to collaborate with an established outfit. According to Leslie Hamilton, writing in WhatItCosts.com, a ballpark figure for a packaged tour would be seventy to a hundred thousand US dollars. That's a bit high. Alpine Ascents currently posts a $65,000 land fee -- i.e., exclusive of travel to Nepal. Dan Mazur's SummitClimb quotes a quite reasonable $30,550 for their 68-day "full-service" climb via the standard Hillary route, and $5000 less for the north-side approach via Tibet. That may be chump change for a commercial hospital tycoon like Edward Cole, but what about the rest of us?

Of course, there are other impediments to an Everest climb. Membership in AARP is not necessarily an automatic disqualifier, but you must have high-altitude experience, be in good shape, and get your doctor's permission. Presumably Edward could browbeat his oncologist into acquiescence, but not too many of us can hop off the couch or out of the bio labs and expect our doctor, much less Dan Mazur, to go along with a Louvre-Pyramids-Taj Mahal-Everest itinerary. And, not to be too literal about a Hollywood movie, but most of us would prefer to check off those bucket list experiences before we kick the bucket, not after.

So, Mark, here's my suggestion. Instead of targeting the #1 peak on Earth, Mt. Everest (about which you will recall that Hillary remarked, It's all bullshit on Everest these days), shoot for #6, Cho Oyu. A bit shorter than Carter's mountain (8201m/26,906 ft as compared to Everest's 8850 m/29,035 ft), Cho Oyu is described as "the most accessible" of the fourteen "8k peaks." And relatively cheap: Dan's full service cost for 2011 is $12,050. That's roughly comparable to one of those Lindblad cruises to Antarctica, and you don't have to book for two -- so there's no problem if Anne-Marie isn't up for it.

Majestic View from Cho Oyu, Camp Three (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

This article is not about Cho Oyu, exactly; but, as an appetite whetter, here's a video clip of a SummitClimb expedition to Cho Oyu:

Now then, let's say you're not a mountain climber, not in great shape, not rich, but twelve grand for the sixth highest mountain, a marquee event on your bucket list, sounds doable. Let's walk this backward, and figure out how to get there.

Right off the bat, you're going to have to put aside all the snarky reasons I gave last month for organizing your own do-it-yourself expedition:

Do you really need someone to meet you at the airport, hold your hand on sight-seeing tours, and keep an effective buffer between you and the ambient culture? Do you want to travel on a moving circus with 25 other tourists? Do you want some porter half your size to carry your load (and probably those of two other "membas") while you saunter along with a fanny pack and a water bottle? Do you want to stay in a tent and have your own chef cook for you, when you could be staying in a nice warm tea-house picking your meals a la carte?

Climbing a real mountain, with multiple campsites and technical obstacles, requires a bit of realism, and the first thing you want to do is locate a good expedition organizer. Which brings me back to Dan Mazur. Many of you will remember the role Dan played in sparking Greg Mortenson's career as the Johnny Appleseed of Pashtun schoolhouses. In Three Cups of Tea, Greg credits Dan with pulling the plug on a nearly complete climb of K2 in order to evacuate an imprudent climber (Etienne Fine) who would otherwise have died. That was back in 1993. In 2006, Dan similarly derailed an Everest assault two hours below the summit in order to evacuate Lincoln Hall, an Australian climber who had been left for dead by his own team and yet miraculously revived after spending the night completely exposed at 8600m. His video clip on YouTube is worth watching.

Daniel Mazur's heroism needs to be put in context. Lincoln Hall's rescue occurred just ten days after forty climbers had walked right past British mountaineer David Sharp as he lay dying in almost the same spot. Sir Edmund Hillary commented that "people have completely lost sight of what is important." (See the New York Times article.) Alone the fact that Dan Mazur has consistently kept sight of what is important puts his company at the top of my bucket-list-organizer list.

Inasmuch as I am plugging Dan Mazur's programs, I should point out that although I have no personal stake in Dan's business, I am a fan of Scott MacLennan, winner of this year's Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Award), who happens to collaborate on Dan's philanthropic Service Trek programs. Since I thought there might be a case to be made in favor of selecting a local (Nepali) outfitter, I asked Scott's advice. His answer:

Dan uses 99% local people for these treks and his climbs. The advantage I think is you have a very, very experienced person in Dan who in turn has been using the same local operators for years and years. You get the security of western safety ethic while still employing the locals. The locals would not, very generally speaking of course, be as committed to safety and logistics as Dan is, would probably either charge the same or charge less and also pay the Nepali staff less. The majority of money with a local company goes to the agency, not the guides, the cooks or the porters. Dan has a long term commitment to his staff; these schools and clinics [Dan's philanthropic projects] are being built in their villages, something else the local person is not very likely to do.

So, I would say that a good place to start planning your Witness Something Truly Majestic project is SummitClimb's Cho Oyu: World's Sixth Highest and Most Accessible 8000 Metre Peak page. Again, Cho Oyu is not for newbies, but here's the beauty part: you can qualify by climbing nearby Mt. Mera. SummitClimb's Mera page,Trek, Walk, Hike, Climb Mera Peak: Affordable & Easy Way to Reach 6500 Metres, notes that the program includes instruction in everything you need to know about climbing during the trip to safely ascend this fun trekking peak, and specifically mentions that successfully climbing Mera Peak could qualify you for Cho Oyu. And if you decide you can live without the glory of an 8k summit, Mt. Mera itself is a worthy Bucket Lister.

Why Mera? It's big, cheap, and easy.

Big. Mera (6,475m/21,246ft) is the highest of Nepal's trekking peaks. That classification is conferred by the Nepal Mountaineering Association (NMA) on sites under 7,000m/ 22,970 ft that theoretically are climbable by anyone with a moderate amount of mountaineering experience and skills; no specific prior experience is required at all ... to get permission. Survival is another matter. As usual, relativity is deceptive. On any other continent, in any other range but the Himalayas, Mera would be a majestic giant. In fact, Aconcagua, the tallest peak in the Andes and the tallest outside the Himalayas, is only a shade higher (6962m/ 22,841ft). Denali (Mt. Washington), tallest peak in North America, is 6198m/20,335ft. Both Denali and Aconcagua, if they had happened to erupt in Nepal, would be mere trekking peaks.

Cheap. You do need a permit for a trekking peak, and you have to pay a fee, according to whether the peak is Group A or Group B. Mera is in Group B, and the current fee is $350 for one to four people. The paperwork is simple, but must be done in Kathmandu, so you'll have to be there for a few days if you are making your own arrangements. Anyway, if you know so little about trekking and climbing in Nepal that you are actually reading this article, you should book with a group. SummitClimb's full-service cost for 2011 is $3050.

Easy. Again, this is a relative concept. Now might be a good time to underline that I have not climbed either Cho Oyu or Mt Mera (or any other trekking peak) ... which is why they qualify for my bucket list. The SummitClimb Web site calls Mera a fun trekking peak, but, again, Mera is not exactly a piece of cake. There are quite a few highly technical approach routes, some still unclimbed. The most popular route, straight up the main glacier, is relatively easy... if you know how to avoid crevasses, altitude sickness, and suddenly inclement weather. Legally speaking, you don't have to book a tour, but since all routes involve uninhabited valleys, you're going to need to hire help to get there; you might as well get the kind of help that will make sure you come home alive.

Mera Itinerary:

Here's the day-by-day SummitClimb program for the Mt. Mera trek and climb. Of course, you can arrive in Nepal earlier or leave later -- those arrangements are up to you.

Day 1: Orientation day in Kathmandu (1300m/4,250 ft).

Day 2: Fly to Lukla (2860 m/9,400 ft).

Day 3: Trek through rhododendron forests from Lukla to the village of Chutanga (3474 m/11,400 ft).

Day 4: Trek across the Zetra La pass (4600 m/15,100 ft), to the village of Chatra La (4200 m/13,800 ft).

Day 5: Descent into the Hinku River valley, through rhododendron and pine forests; the trail zigzags along the river to Kothey (Tashi Ongma), "an oasis of green, waterfalls, and fresh fruit" at 3500 m/11,500 ft.

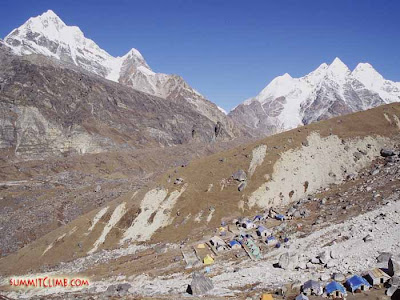

Camping in the Hingku Valley, 3500m (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Day 6: First glimpse of Mera towering at the end of the valley. Continue through forests along the river to Tagnag at 4300 m/14,100 ft.

Day 7: Rest day, acclimatization, explore the area around Tagnag.

Day 8: Walk to Khare village (5000 metres/16,400 ft).

Day 9: Trek across the Mera La pass (5300 m/17,400 ft) to Mera Peak basecamp (5100 m/16,700 ft).

Toward Mera Base Camp (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Day 10: Rest day, acclimatization, explore the surrounding area.

Base Camp, near Khare (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Day 11: Climb to Mt. Mera High Camp (5768 metres/18,978 feet).

Between Base Camp and Mera La (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Between Mera La and High Camp (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Day 12: Summit Mera Peak (6476 m/21,246 ft), descend to Khare.

Summit from High Camp (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Approaching the Summit of Cho Oyu, 6300 m (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Final Pitch on Mera (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Dawa Sherpa on Mera Summit (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Day 13: Extra day for second summit attempt and packing up, resting, or whatever.

Day 14: Trek back from Khare to Tagnag.

Day 15: Trek to Kothey (Tashi Ongma).

Day 16: Trek to Chatra La or Chutanga.

Chutanga Camp (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

Day 17: Trek to Lukla. Teahouse or camping.

Day 18: Flight to Kathmandu. Best to leave yourself a day or two extra before the flight out of Kathmandu; delays at Lukla are common, and you may need the time for Christmas shopping, celebrations, and secondary bucket list items. Over and out.

The SummitClimb itinerary represents the minimum time commitment for a safe Mera ascent. I would say that many first time trekkers will have difficulty handling the program if they just leap off the couch onto a plane for Kathmandu and immediately fly off to Lukla. The Long Trek In from the roadhead at Jiri to the airstrip at Lukla takes about nine days, but is great for conditioning. It won't mitigate the risk of altitude sickness, as you don't get much higher than 3600m/11,800 ft (at Lamjura Pass), while you'll need to survive 6476 m/21,246 ft. The best strategy is to leave yourself time to do the full Everest Trek, up to Kala Pattar and Everest Base Camp. That will tack on another ten days or so, but you'll be in great shape, your red blood corpuscle count will be burgeoning, and you'll stand a good chance of enjoying your "fun trekking peak." And, if you choose, of moving on up to Cho Oyu.

Summit client on Mera La, 5400 m (Courtesy of SummitClimb)

If not, climbing Mt. Mera -- whether or not you stand on the top -- is pretty cool. You will definitely have Witnessed Something Truly Majestic.

In fact, I would argue that the Long Trek In to Kala Pattar (in the Everest cirque) is itself a bucket-worthy adventure. Visually, the majesty of Mount Everest (like that of elephants, walruses, and kings) is most convincingly experienced from below. In addition, the opportunities for participatory tourism, and for life-changing experiences, are much more abundant in the villages of Nepal than on the shimmering peaks. The late Tony Freake, who won the Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Award for his work in Phortse, first visited that village while trekking around the Khumbu in order to acclimatize himself for the Mera climb. See Participatory Tourism: Climber Adopts Village.

If you can't do a preparatory trek, you can still improve your chances of having fun on Mera by committing yourself to a fitness program. Here are some suggestions from Dan Mazur's colleague Stewart Wolfe:

- You should always consult your doctor before starting a rigorous exercise plan.

- In the beginning, to see how you handle the training, and to avoid muscle strains that could slow your training down, you may wish to use shorter, more frequent, but less taxing workouts, and take more rest. After you get "up to speed," you can increase the rigor. Also remember that swimming is an excellent form of training because it does not put stress upon your joints.

- In order to train well for your trip you should work toward exercising three to four times a week for between 40 and 90 minutes. You should expect to work hard: keep your heart rate high and your breathing heavy.

- Adequate rest (7-8 hours of sleep) and a well-balanced diet are essential if you want to avoid injury and illness before the expedition. Stay hydrated: aim for four liters per day.

- Consider hiring a personal trainer; these professionals are expert at motivating you to achieve a higher level of fitness without injury.

- Utilizing both gym equipment and the great outdoors will provide a more balanced exercise program. You should try to accomplish at least half of your workouts outside. Hillwalking and climbing with a pack weighing 5-10 kilos/10-20 pounds is essential. No hills around your home? Don't overlook stairs, bleachers, viewing stands, stadiums, even stairways in tall buildings.

- About six weeks before the expedition departure date, you may wish to do one full day each week of hill walking, climbing or some equivalent, with a light rucksack. On that day, you would want to work toward six to eight hours of continuous walking or climbing up and down hill, with four to six ten-minute breaks and a 1/2 to 1 hour lunch break midway through. To minimize the risk of injury, start with a half day and increase gradually to a full day, once a week.

- When carrying a backpack downhill, reduce your load a bit, and always keep your knees flexed. Jamming your knees to slow down can cause an incapacitating variety of bursitis known among Nepal trekkers as "Sahib's knee." One way to lighten your load, by the way, is to carry a couple of liters of water on the way up, and drink it before you descend.

- For more information on how to train for a SummitClimb expedition email Ben Palmer: ben[at]benpalmerfitness.co.uk. Ben is nice guy, an avid climber, and uncommonly qualified as a personal trainer, with four years' experience as a Premier Global Level III Personal Trainer, the highest qualification available.

If any of our readers are interested in forming a Bucketlist-Mera Support Group, let us know. How about it, Mark? You in?

Seth Sicroff, Nepal Editor for Wandering Educators

Manager, Sunrise Pashmina

Photos courtesy and copyright Summit Climb.

Feature photo:

Mera from Base Camp (Courtesy of SummitClimb)