In an earlier article, Bucket Listing Mt. Mera, I suggested that some of you who are working on your Bucket List might consider substituting Cho Oyu (8201m/26,906ft) for Mt. Everest in the “Witness Something Truly Majestic” category; I then went on to recommend Mt. Mera as the ideal training peak for a Cho Oyu attempt. In this article, the ostensible topic is Cho Oyu, but the main theme is broader: Why would anyone want to climb Mt. Everest – or any other lethally gigantic mountain?

"Because it's there."

So George Mallory is reputed to have answered someone who asked why he wanted to climb Everest -- last famous (if not famous last) words, given that a few weeks later (in June 1924) Mallory disappeared somewhere near the summit. As the owner of an Irish Wolfhound, world tallest dog breed, subject to a daily barrage of horse jokes ("That's not a dog, it's a horse"; "Got a saddle for that thing?" etc., etc., etc.), I can appreciate the beauty of a snappy, slightly abrasive come-back to a dumb question. On the other hand, Mallory's quip does tend to gloss over some pertinent factors.

George Mallory, photo courtesy of Wikipedia

First of all, let’s try to unpack what Mallory meant. Clearly, he was not suggesting that he might be drawn to climb anything that was “there” – meaning “in existence.” That kind of attitude would leave one in a perpetual state of exhaustion… unless, arguably, one were living in Oakland, California, about which Gertrude Stein wrote, “There is no there there.”

One possible interpretation of Mallory's remark is, "It's there and no human being has been there before." At the time, that attitude was more common than it is today: people understood that there were large areas of the globe that we knew nothing about, and "explorer" was a plausible vocation. Of course, most exploration was motivated by greed, whether the object of desire was spice, gold, fur, slaves, land, or a fungible variety of fame.

What Mallory likely meant was, “I want to climb it because it is the highest mountain in the world, and because by doing so I will not only partake of the mountain’s superlative status but also become world famous and at least a bit happier.”

The allure of superlatives and numerological bragging rights may explain why Mallory's line has seemed somehow sensible to a thousands and thousands of aspiring Everest summiteers long after Edmund Hillary declared that he and Tenzing Norgay had "knocked the bastard off." The list of headlines is seeming inexhaustible: oldest, youngest, first with such-and-such physical handicap, first by such-and-such route, first traverse, first solo, most ascents, fastest, first overnight bivouac at the summit, first ascent without oxygen ... all multiplied by two (separate records for men and women) and by more than 200 (all the countries that have existed since 1953). Climbers are now busily collecting the entire set of 14 peaks over 8000 meters, and the folks at Guinness seem inclined to oblige an infinite regress of obsessions.

Newsflash: In my Mera article, I reported that a retired Nepali soldier, Min Bahadur Scherchan, held the record for oldest summiteer; he was 76 years and 340 days old when he summited on May 25, 2008. Shortly afterwards, Yuichiro Miura (a mere 74-year-old, who however held the record for first skiing Everest back in 1970) snatched Sherchan's glory away when Guinness agreed with him that Sherchan had failed to complete all required formalities to validate his record. Discovering that his record had been usurped, Sherchan traveled all the way to Guinness's London office with a new set of documents to nail down his claim and reclaim the record. Your move, Miura!

Numerology notwithstanding, Mallory's dictum cannot possibly explain the appeal of Everest (and those thirteen other superlative peaks) to the multitudes of climbers who are presumably aware that they have absolutely no angle to parlay into a wedge of the 15-minute spotlight. So why do they knock themselves out?

In order to understand this drive, which arguably is the foundation of Nepal's tourism industry, and to understand why you yourself may decide to bucket-list Cho Oyu, we need to have a clear sense of exactly how unpleasant an 8000-meter climb is going to be. In the next paragraphs we will trace the route followed by an expedition fielded by Dan Mazur's Summit Climb company, highlighting at each step the specific challenges that many of us would find nightmarish.

Getting There

Cho Oyu (<Jomo Yu, Lady Turquoise), sixth highest peak in the world, is often referred to as the “most accessible” of the fourteen 8000m peaks. That may be true: for one thing, you can drive all the way to the Old Chinese Base Camp (OCBC) in Tibet. There are also very few technically difficult spots, and, in ideal conditions, an acclimated climber who knows how to use crampons and jumar can handle them without problem. But the fact is that Cho Oyu is no walk in the park. Expeditions often turn back without putting anyone on top; people get sick or injured; and quite a few people have died and more will certainly die. Unless you are a professional climber, you will want to sign up with a reputable expedition organizer such as Dan Mazur.

As I pointed out in Mera article, I have never been above 5750m/18,665ft. That's high enough to have personal knowledge of a few of the pertinent challenges, but the specific details below are based largely on SummitClimb expedition reports and on Tim Boelter's movie Cho Oyu: West of Everest (CO:WoE), which documents one of Dan Mazur's expeditions back in 2000.

Signing up with Dan means that you will never notice, or be only vaguely aware of, many of the unpleasantnesses of an 8000-meter climb. The bureaucratic hassles alone would be daunting. Engaging porters and guides; gathering, packing, transporting, sorting, and distributing several tons of gear and provisions, much of which will have to be trucked from Lhasa to base camp via high passes where breakdowns and delay are common; deploying and maintaining communications systems; planning for the evacuation of sick or injured personnel, maintaining a balance between prudent redundancy and streamlined mobility; foreseeing and forestalling conflicts and maintaining team cohesiveness: each of these stressful challenges could lead to failure to summit -- or much much much worse -- and explain why expedition organization should be left to professionals.

So, let's just focus on the problems facing a client on a well-run packaged expedition to Cho Oyu.

"It's a lot about hard work, a lot about sacrifice, a lot about doing things that you'd never do, and above all working extremely hard in very very difficult conditions and situations." [Climber, CO:WoE]

The first stage of the adventure is the ride to Old Chinese Base Camp. By the way, the fact that you can actually drive right up to the mountain could be an important reason to bucket-list Cho Oyu rather than another 8000m peak with a ten-day walk up: it means you can squeeze a climb into a one-month vacation window, rather than postponing the thing until you retire.

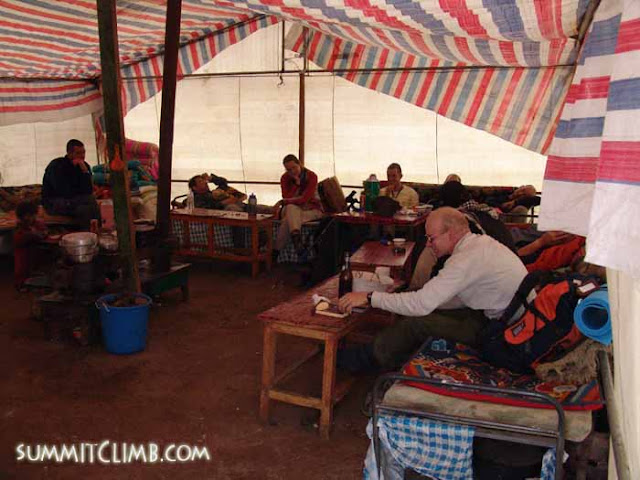

Teahouse - Old Chinese Base Camp, on the northern approach to Cho Oyu

From Kathmandu, the expedition bus goes west along the so-called Arniko Highway, which also leads to the Everest trailhead at Jiri. However, instead of continuing on the Swiss-built extension to Jiri, we go north to Barabise and then Kodari on the Tibetan (Chinese) border. "Highway" is a relative term, of course; none of it is wider than two lanes, and as the road enters the Bhote Kosi valley, it is barely wide enough for opposing traffic to squeak by. Under ideal conditions, the 115-km stretch takes about four hours. Unfortunately, in order to avoid winter storms, expeditions generally have to move out before the summer rainy season has dribbled to a close. Inevitably the road is cut in several places by landslides. In some cases, the vehicles can slosh through the mud, but normally there are a few spots where the team has to get out and push -- or hire locals to do so. That's under ideal circumstances. Quite frequently, the trucks have to be unloaded, everything bundled onto porters and reloaded onto other conveyances somewhere down the road. Sometimes several times. In fact, landslides have become an important component of the regional economy.

Once the team has crossed into Tibet, the road remains problematic, climbing through the steep Bhote Kosi gorge to Nyalam (3750m/12,300ft), the first overnight pit stop, and then on to the Tong La pass (5120m/16,800 ft) at the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. The overnight at Nyalam is important for acclimation, which is an increasingly signficant factor as the expedition continues onward. Even with the prescribed acclimation days at every stage, most members of the team will suffer some of the symptoms of altitude sickness. These range from loss of appetite and insomnia to fatigue, headaches, and the so-called Khumbu cough. This cough, which nearly everyone experiences at some elevation or other is caused by the irritating effect of cold dry air on the lungs; it can be severe enough to cause broken ribs. Acute mountain sickness may present as pulmonary edema (similar to the bends) and/or cerebral edema, entailing fluid build-up in the meninges. Both are extremely dangerous, and many climbers who would appear to be in excellent health are forced to evacuate or die.

Allowing for acclimation stops at Nyalam and Tingri (4390m/14,400ft), the expedition will reach Old Chinese Base Camp (4785m/15,700ft) after five days of travel. There the equipment is unpacked, sorted, and repacked into yak loads. The yaks will do most of the grunt-work on the two-day trek up a moraine-strewn glacial valley to Advance Base Camp (18,368). Although the horizontal distance is only eleven miles, the altitude gain is enough to warrant an intermediate camp.

Cho Oyu summit from Advance Base Camp

ABC at Cho Oyu is quite high -- a good thousand feet higher than Everest Base Camp. At that altitude, the body is falling apart. Recovery from minor health issues is slow, and fatigue is a constant companion. The team will spend a couple of weeks slogging up and down the mountain, carrying equipment from Advance Base Camp and setting up the three higher camps, always returning to ABC to recover strength. On the mountain, dysentery is common. Some believe it is in part due to the large number of teams: human waste is inevitably polluting the water supply. Diarrhea, cramps, vomiting, headaches, and fever are more than nuisances; dehydration alone can be fatal, and failure to maintain caloric intake can lead to hypothermia. Symptoms can cascade, with minor colds quickly developing into dangerous bronchitis. Prior successful experience is no guarantee that a climber will successfully acclimatize on a high Himalayan peak.

Advance Base Camp, Cho Oyu

Camp 1 (5600m/18,368ft) is reached after a long up-and-down trek over rocky moraine followed by a grinding haul up a scree slope described by Dan Mazur as "1500 feet of kitty litter." From Camp 2 (7000m/22960ft), it's all snow and ice. The route follows a ridge, up to a 25-foot ice cliff. The angle is around 70 degrees, but there are cut steps and fixed ropes Still, there are occasionally bottle-necks of up to two dozen climbers strung out along a single overburdened line, with neophyte climbers apparently confronting jumars (the mechanical devices used to grip the rope) for the first time. Injuries can occur from falls as well as dislodged ice.

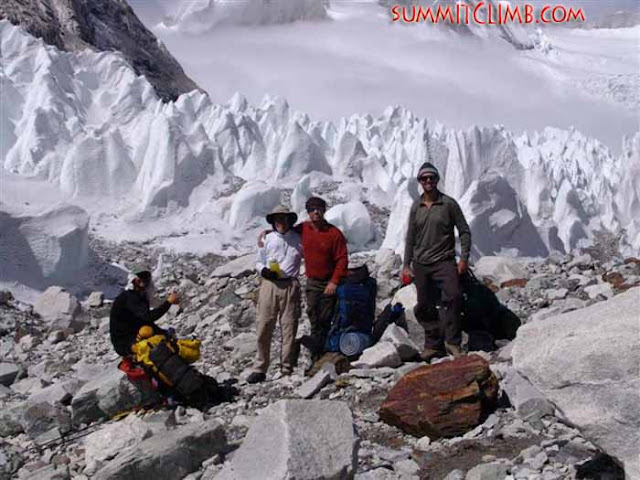

Glacial Moraine Above Advance Base Camp, Cho Oyu

After the ice cliff, the route veers right on a little plateau, then reaches another steep headwall, turns a corner and runs up to Camp 2 (7,000 metres/23,000ft). None of it would be particularly difficult were it not for the elevation, but fatigue and poor judgment can endanger everybody.

Camp 2, Cho Oyu

After Camp 2 , there is a 1480' ascent to a prominent knoll, followed by another slope up to the site of Camp 3 (7452m/24,450ft). The site is exposed to brutal winds, and set-up can be a challenge. Partly this is a function of altitude, but mountain weather is notoriously fickle; an early winter storm can strike with little warning, making life miserable even in base camp.

At this point, the struggle is as much mental as physical. Every step becomes an act of will. "Unless you've been up there, you have no idea how hard the altitude will hit you. Things move real slow... You're hiking up, you gain 500 meters, and six or seven hours have gone by. Time seems to be suspended." [Climber, CO:WoE]

Camp 3, Cho Oyu

From Camp 3, the climbers launch their summit bid in the middle of the night. Moving out so early is not in itself a hardship: the tent and sleeping gear cannot keep a climber warm, the noise of the tent sides flapping in the wind is literally like the roar of a jet, and the elevation and lack of oxygen prevent most people from sleeping effectively. Still, climbing in the dark is inherently dangerous. The headlamps cast only a small circle of light; the unlit areas seem darker by contrast, and the shadows can be deceptive enough to make a climber stumble. Descending in the dark, however, is infinitely more dangerous, as a stumble can easily turn into something worse. It's only the urgency of getting back down to a camp before nightfall that forces the climbers to set out well before the break of day.

"The average person who's never done this before has no concept of the hard work and the mental peace that it takes to get your boots and crampons on at 7500 meters. On a good day, it may take you an hour. And that's not uncommon." [Climber, CO:WoE]

Above Camp 3, there is a ten-meter rock step -- again, not an extremely difficult obstacle in itself, but treacherous at that altitude, and at night. A one-hour traverse of the summit plateau brings the climbers to their objective -- a slight rise, most notable for the view of Mt. Everest towering above the other giants of the high Himalayas.

Summit of Cho Oyu

Getting Back

We won't have much to say about the descent in this context, but reaching the peak is only part of the program. More climbers die coming down than going up. On the CO:WoE climb, Dan Mazur's team made it back with no deaths and no serious injuries, in large part due to his company's emphasis on risk reduction. However, a Montenegran climber whom his team rescued ended up dying in Advance Base Camp. According to the online in memoriam notice, Pavle Milosevic left behind a "9-year-old daughter, Iva, and a lot of friends full with the fondest memories of him."

The list of physical risks could be extended -- we haven't even mentioned avalanche, frostbite, or snow-blindness. Social contretemps tend to have immediate physical concommitants. Interpersonal conflict is both a cause and result of stress. Different climbing styles, time constraints, and selfishness can lead to arguments, equipment theft, and, most dangerous, separation of climbing partners.

So here's the question, again: why do it? I'm not saying that climbing high mountains doesn't have its pleasures. There are spectacular views, and collateral payoffs: friendships, teamwork, physical and mental achievements, among others. Whether these measure up to the risks and the hard work is a matter of personal taste. Of course, lots of sports entail risks -- think of football, rugby, skiing. Some entail pain and discomfort: marathons and boxing, for instance. But what other recreational activity actually guarantees suffering? Who would ride a roller coaster, go to Disney World, or eat at a five-star restaurant if it meant definitely enduring a common cold or a case of the runs?

For obvious reasons, SummitClimb does not include an answer to this question in its marketing strategy, nor does CO:WOE directly address the issue of motivation. However, there are a number of revealing comments. Here's what one of them had to say:

"If you're going to stand on the top of these big mountains, you have to be ready to have setbacks, you have to be ready to be sick, you have to be ready to be frozen, and then you come back down and refurbish yourself, find an inner peace, and then figure out how you're going to get up the mountain. Expeditions are all about challenging yourself, about finding who you really are, about raising your personal bar." [Climber, CO:WoE]

As a personal game-changer, mountain climbing is a reflex of ritual behavior and mythic narrative deeply embedded in the human psyche. Let's look at some other examples.

Mountain Climbing as Game-Changer

At the conclusion of the sixth book of his de Republica (On the Commonwealth; 54BC), Cicero relates the Dream of Scipio. This Scipio is the general Scipio Aemilianus Africanus (185–129 BC (a.k.a. Scipio Africanus the Younger), and in Cicero’s story Scipio relates a dream in which he meets with his illustrious adoptive grandfather Scipio Africanus (Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, 235–183 BC) who had defeated Hannibal in the final battle of the Second Punic War, following the latter’s incursion into the Roman peninsula via the Alps. Looking down on Carthage “from a certain bright and shining place on high, full of stars,” Scipio the Elder reveals his grandson’s destiny (the destruction of Carthage) and advises him on the treacherous political situation awaiting him back in Rome. Then Scipio’s dead father appears. Looking around, the dreamer realizes that he has ascended to a place far above Earth. His father gives him an extensive lesson in Ptolemaic cosmology and Stoic philosophy. The younger Scipio learns that his life has been unfolding in a tiny place, a scrap of land dwarfed by the extent of a world much of which has never even heard of him, on a planet itself dwarfed by the other celestial bodies, constellations, and the entire Milky Way. Scipio’s father urges him to reassess his priorities and his life in this larger perspective, to turn his mind away from “pleasures of the body” and instead dedicate himself to his country’s welfare. Scipio promises that he will strive much harder to do so.

This fictitious narrative may seem obscure and beside the point, but it had repercussions that still ripple and resound in modern times. A fourth-century AD commentary by Roman grammarian and philosoper Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius (395–423 AD) was used by the sixth-century philosopher Boethius, who became popular in the medieval period; Chaucer and Dante are just two of the more notable authors who reworked Scipio's Dream. But we're not just talking about elite literature. Scipio's vertical quest for enlightenment is part of a narrative template that predates history and occurs in all cultures.

The Persephone and Demeter myth, widespread in Greek and Roman antiquity, was about the abduction of the daughter (Persephone) of the goddess of agriculture (Demeter; a.k.a. Ceres, as in cereal) by the god of the underworld. After a protracted search over hill and dale, during which the distraught goddess completely neglected her fiduciary responsibility to farmers, Demeter caught up with her daughter in the underworld. However, since Persephone had eaten six pomegranate seeds while down under, she could only return to her mother for six months of the year. Beyond serving as an origin myth, explaining the origin of seasons, the myth was associated with the Eleusinian initiation rites. These involved a protracted procession, presumably under the influence of a barley brew, leading up to secret "mysteries" (< mysterium <ministerium) in the inner sanctum of the temple in which a life-changing truth (some argue that it was related to the use of an LSD analog derived from rye ergot) was administered to the initiate.

Rituals are basically magical gestures designed to control the cosmos, whether in a broad sense (as the Germanic fruit-decked evergreen tree displayed at winter solstice was supposed to remind the cosmos that enough was enough and it was time to start preparing the return of prosperity and abundance) or in a narrow sense (as the throwing of rice is supposed to fecundate the bride). Cultural anthropologists have long been aware of the intricate connections between ritual and myth. In some cases, rituals are generated to commemorate sacred stories; a good example would be the Catholic communion rituals relating to the crucifixion of Christ. In other cases, myths are generated to justify and preserve the structure of a pre-existing ritual. This is probably the case with the Persephone and Demeter myth that grew up around the Eleusinian mysteries.

In the recasting of god-based narratives as anthropocentric epics, legends, and fairy tales, some aspects of the crucial vegetal cycle myths necessarily changed. The purpose of the quest was not the return of agrarian abundance; instead, the hero would be looking for treasure, bride, the golden fleece, or something more abstract: restored honor, happiness, or wisdom. The humanoid hero obviously could not die on the mission, but he could have a near-death experience, or a close associate could be lost. Still, the heroic quest is recognizable as a recurring monomyth, with a panoply of typical themes. Here are a few:

- the challenge, or call to adventure

- the equipping of the hero, generally with special weaponry

- arduous voyage to the Other World

- help given to a random stranger who turns out to be useful later on

- conflict, often involving death or near-death

- acquisition of a transformative prize

- return voyage, with more adversity

- homecoming, wearing the "weeds of the Other World" -- sometimes a disguise

- testing and recognition of the hero

- sharing or application of the acquired boon or prize

There are many other typical motifs, which may or may not be present in any given version of the universal story. Well-known questing heroes include Moses, Hercules, Jason, Tristan, Quaid (Arnold Schwartzenegger's character in Total Recall), Jack (of beanstalk fame), Shrek, and of course Dora the Explorer. Sometimes, as in the Odyssey, the transformative prize is simply survival. As the heroic monomyth entered elite literature, many elements were deliberately inverted; in the Lord of the Rings, the quest was undertaken to get rid of the ring rather than to acquire a prize. Instead of the hero, we may have an antihero, as in Catcher in the Rye; and the hero may go unrewarded -- so long as the reader gains in the process. Still, whatever the changes, the net effect of the quest is almost always reassessment and redirection of the hero's life, with ancillary advantages to his family, cohort, tribe, or country. In some cases those advantages don't accrue within the narrative itself, but the impact is broadened in the retelling or reading of the story. This is especially true of stories in which the transformative prize is wisdom.

So far we've been talking rather loosely about the "Other World." In ancient traditions, that Other World, generally identified with the land of the dead and/or the land of supernatural entities, could be located in any remote place: across the ocean, on an island, underground, in a hidden valley, or in the sky. Great mountain ranges and peaks have often been venerated as the abode of the gods; sacred mountains are found everywhere on Earth, from Uluru (Ayer's Rock) in Australia to Kailash in Tibet to Olympus in Greece to Devil's Tower in Wyoming. Both Buddhism and Hinduism emphasize the importance of Himalayan pilgrimage. The all-sapient hermit perched on a mountain top is a cliche of modern culture. Since most of the world is now presumed known and non-Otherly, mountain peaks are the default destinations for heroic adventurers.

Heroic stories are intended to inspire. Readers may aspire to share vicariously the "lesson" acquired by the hero, or they may try to duplicate or otherwise imitate the hero's adventure so as to arrive at their own version of the prize. Does this mean that Himalayan climbers secretly fantasize themselves as Promethean culture heroes? Not at all. Certainly Ed Hillary did not harbor grand expectations about the impact of his team's quest (although Sir John Hunt, the expedition leader and, arguably, the true hero, may have); both he and Tenzing were shocked at the fuss made about their little adventure. Ironically, Sir Edmund subsequently took on the heroic mantle of the Promethean hero, bringing schools, clinics, and an airport to his adoptive people, and in the process serving as a challenge to succeeding generations of heroes to follow his model.

They, however. may not even consider the tradition with which they are aligning themselves. After all, when a new photographer rushes out to shoot sunsets and butterflies, he is not aware that these cliches exist in his mind as templates precisely because he has been surrounded by them all his life. We are programmed to respond to tradition, not to be original. That's not a bad thing: cultural cohesion depends on it. Consciously or not, tourists (including adventure tourists) seek to replicate travel patterns that have been validated by popular books, movies, and television programs -- not to mention famous quips like Mallory's and real-life heroes like Maurice Herzog and Ed Hillary; they are also sensitive to expectations when they return from their otherworldly adventure, particularly one with a near-death experience, and often conform to the heroic model by giving slide lectures. Of all the available travel templates, including "if it's Tuesday this must be Brussels," three nights and two days in Cancun, snorkeling on the Great Barrier Reef, our culture tells us that a Himalayan climb is most likely to be a transformative experience.

Ice Step between Camp One and Camp Two, Cho Oyu

Cho Oyu: There is a Point.

Here is the point: It's relatively easy to forget that heroism and honor are not on the line when you undertake to climb one of these charismatic mountains. Yes, there is a certain mythic resonance, and the imaginative overlay of heroic quests foments a level of self-reflection unusual for most people. Is this a do-or-die opportunity? I say no. It's probably not even worth a couple of toes. Make sure you book with a professional like Dan Mazur who will help you understand that knowing when to turn around is an essential part of the mountain's lesson. We'll never know if Mallory made it to the top of Everest, and frankly I don't care. Getting there doesn't count if you don't get back.

Seth Sicroff, Nepal Editor for Wandering Educators

Manager, Sunrise Pashmina

Photos courtesy and copyright of SummitClimb.com, except where noted