Not all of China eats rice: The divide between North and South

China is famous for being one of the most food-oriented cultures in the world. With intricate and time-consuming recipes, and an abundance of symbolism hiding behind every dish, there is no question that Chinese meals are more than just the sum of their parts. But Chinese culture is not homogenous, and their food culture is even less so. Different religions, social classes, and generations can create different food styles, but in China, geography figures more prominently: the north is famous for wheat, while the south primarily consumes rice.

Rice terraces. Photo: mckaysavage

In China, wheat and rice constitute a large portion of every meal, much like westerners use meat. Wheat and rice are used to keep 'balance' in the meal. It keeps heavy and light in check, and softens flavors. While it may be too much of a generalization to say that there's a sharp divide created by the Yangtze river, it is true that there is a dramatic difference in the food cultures of the north and south.

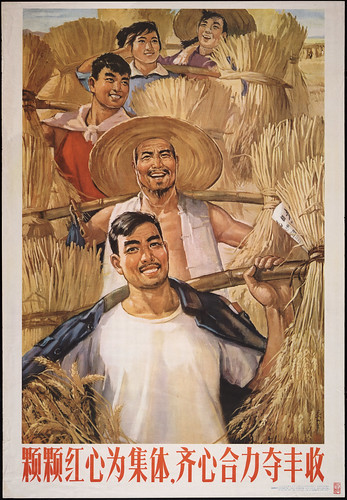

1965 poster, harvesting wheat in China. Photo: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto

The history and basis of this division goes back to the Qin dynasty, and is ingrained in the land. Originally the north subsisted mainly on millet (called the first of the five grains consumed in the north), wheat (which started becoming important in the Zhou dynasty, after being brought in from Vietnam), beans, and hemp. Rice, although not as common, was available, and was mostly consumed by the wealthy. Rice was harder to grow because of the drier northern lands, and was therefore less prominent. Since then, the north has become dramatically drier, making it a harder area to grow rice, while the south remains hospitable to growing rice. During the Qin era, the Huai river served as a transition area, where wheat and rice were equally common. To the north of the Huai was predominantly wheat and millet, while to the south was mostly rice.

During the Age of fragmentation, rice spread north as wheat spread south, beginning a reversal. This started in 318 when a southern court ordered for wheat to be grown. Since wheat was a rarer commodity, it was intended as a sign of prosperity in the area. Unfortunately all the wheat fields failed - most were eaten by locusts. They continued to attempt to bring in wheat, until wheat became a substantial part of the diet. After 4 famines between 330 and 400, they switched wholly back to rice. Meanwhile, in the north a rice culture was being born. After their rice crops failed due to several small droughts, there was a devastating famine in 444. Soon after, the north returned to growing the wheat that flourished in their dry climate. Over time, millet all but disappeared.

China's food cultures extend well beyond the puzzle of their starch history, but this is one of the most distinct differences. Rice and wheat have created very different palates in the north and south, and have helped shape different customs, like dumplings in the north - and the famous noodle stands on every block in the south.

Preparing dumplings. Photo: Paul Arps

Chongqing Hot and Sour Sweet Potato Noodles Stand. Photo: Prince Roy

Anne Driscoll is a member of the Youth Travel Blogging Mentorship Program

All photos courtesy of flickr creative commons