Lighthouses of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

From 5/26/22 through 6/8/22, you can get a free 211-page PDF of Exploring Michigan’s Upper Peninsula Coasts. Go to author Julie Royce’s website at www.jkroyce.wordpress.com. Click the button on the sidebar and provide your email. Your email will be deleted once the book is sent. If you like the book, tell your friends and suggest they get the free PDF or buy the book on Amazon. Better yet, if you like it, write a review on Amazon. Let’s promote Michigan!

Exploring Michigan’s Sunrise Coasts, Exploring Michigan’s Upper Peninsula Coasts, and Exploring Michigan’s Sunset Coasts are available at Amazon.

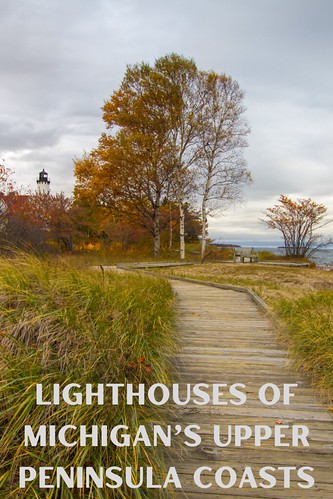

The traveler to Michigan's coastlines will be rewarded with the opportunity to visit many iconic lighthouses. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan's Sunset Coasts, Sunrise Coasts, and Upper Peninsula Coasts, they added a bit of delight and historic perspective to the trip. Below are some of my favorites.

Point Iroquois Light Station

13042-13260 W Lakeshore Drive, Brimley

Traveling the Lake Superior shoreline between Brimley and Whitefish Point on the south tip of Whitefish Bay, you’ll come to the Point Iroquois Light Station and one of the oldest lighthouses guiding ships along the Lake Superior shoreline.

Lighthouse refers to the tower itself. It contains the lantern room with the lens that shines its light. A light station is the property around the lighthouse and it may contain multiple outbuildings in addition to the lighthouse tower. A light station often includes the keeper’s dwelling and an oil house, maybe a barn, boathouse, and a fog-signaling building.

The onsite volunteer staff at Point Iroquois is a repository of information about the history of the lighthouse and the area. The lighthouse was named for a famous 1662 battle in which the local Ojibwe, the Original People of the area, defeated their Iroquois enemy at this spot.

The grounds of the lighthouse are perfectly maintained. The interior Captain’s Quarters are restored with period furniture. The climb to the top of the tower rewards you with a panoramic view of the Bay—often with freighters traveling in the distance.

Being the keeper of the light took a special kind of person. The demanding job required attention both day and night. Before being electrified, a large kerosene lamp provided the light source. Keepers refilled the lamp with oil every four hours. The lens had to be kept clean from soot, and the wick needed constant trimming. Point Iroquois was a plum assignment. The house was big enough for the head keeper and two assistants, along with families to help shoulder the responsibility of safely guiding big ships through this dangerous patch of water.

You can walk the shoreline and look for agates and other natural treasures. The pathway to the water has benches where you can sit and soak in the beauty as you revel in the surroundings. The lighthouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. A giftshop is on the premises.

Whitefish Point Light

18335 N. Whitefish Point Road, Paradise

Money Magazine dubbed the museum on the lighthouse property one of the best small museums in America. Numerous other accolades confirm it is a special place to visit.

Lake Superior around Whitefish Point is a treacherous shipping channel that has earned the unflattering and harsh nickname “Graveyard of the Great Lakes.” The museum dedicates its existence to making shipwreck legends come to life. Through artifacts and exhibits, you piece together the stories of vessels and sailors who braved Superior’s wrath, too many of whom didn’t live to tell about their experience. The video theatre provides a short film documenting the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald and the efforts that raised her bell and made it part of the museum.

The museum store has a selection of lighthouse gifts, art, and books for those interested in maritime history and shipwrecks.

More than 300 species of birds have been recorded at the Whitefish Point Bird Observatory. You may spot songbirds, raptors, shorebirds, and water birds from the observation deck. The land and water features of Whitefish Point create a natural corridor that attracts thousands of birds during spring and fall migrations. The flocks use the area as a stopover habitat to replenish their energy before continuing across Lake Superior. The migrations are not only opportunities for observation, but a chance to enhance education, research, and conservation. Among the species that migrate are golden eagles, peregrine falcons, and boreal owls. The area has been a nesting site for the federally endangered piping plover.

The Whitefish Point Light marks the southeastern end of Lake Superior’s Shipwreck Coast, which stretches west to Munising. This dangerous part of the lake has claimed over 550 ships. More than a third of those lie on the bottom near Whitefish Point at the critical juncture where they entered or left Superior.

In 1849, the lighthouse first sent its beacon light into the fog of the night, and it has remained in operation ever since, making it the oldest operating lighthouse on Lake Superior. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. The Whitefish Point Underwater Preserve protects many of the shipwrecks, which are available to sport divers. The lighthouse is open seasonally for visitors.

Crisp Point Lighthouse

1944 Co Hwy 412, Newberry

This gem may be the highlight of your trip to the U.P. One of the original four Lake Superior Light Saving Stations, the Crisp Point Lighthouse was first proposed in 1896, approved in 1902, and became operational in 1904. It stands 14 miles west of Whitefish Point—but don’t assume it’s a quick drive.

Hidden deep in forested lands, getting to the lighthouse—arriving at that opening where the lake looms ahead—may prove a testament to your determination. You better be driving a four-wheel utility vehicle. No Mercedes, tiny Miata, or sissy car should attempt the trip.

Follow lighthouse signs from M-123. Bumpy roads may force you to consider turning around at several junctions. This is not a well-marked route. You will come to stops where you are unsure which way to go. Each time, convince yourself to push on.

There are bears in the woods around you. You may not see them, but they will be watching you. They are short, close to the ground, and you may think they are just another tree stump. From the treed (or bear-infested) darkness that envelops you, you will finally break out into brilliant sunlight. You are there.

Where is there? A remote Superior shoreline, and if you are lucky, you have the destination to yourself. It is probably the first and only lighthouse where you can open the door and let yourself in. Or where there is a sign telling you to close the door behind you when you leave. You may be the sole soul climbing the tower or scootching out the small entry to the catwalk around the top of the lighthouse. If good fortune smiles on you, you can sit awhile, appreciate the view, and enjoy the tranquility with no one to disturb you.

The author at Crisp Point Lighthouse

Lighthouse lovers are lucky the Crisp Point Light remains standing. Vandalism and the elements nearly caused its demise. Dedicated volunteers poured many hours into restoration to keep this piece of history alive. The outbuildings are gone. In 1998, a thousand cubic yards of stone were placed along the shoreline to help slow erosion, and more stone has been added in several of the years since then. Plans for further stabilization will be carried out as funds become available.

The light is named for Christopher Crisp, one of its colorful keepers. There is a visitor center on the property, a small portion of which is a gift shop. The knowledgeable volunteers will share the history of the lighthouse. Restrooms are available. From the lighthouse property, you can access the rocky Lake Superior beach to search for agates.

Eagle Harbor Lighthouse and Light Station

Lighthouse Road near the swimming beach in Eagle Harbor

Built in 1851, Eagle Harbor Light stands at the rocky entrance to the harbor and remains a working lighthouse, guiding sailors across the northern edge of the Keweenaw Peninsula.

The original lighthouse was replaced in 1871. The octagonal brick light tower is ten feet in diameter. Its walls are a foot thick, and the tower supports a 10-sided cast iron lantern. Lighthouse duties were performed by a head keeper and two assistant keepers. The light has undergone several changes over the years and was automated in 1980.

It is currently a museum filled with period furnishings, open to the public, and operated by the Keweenaw County Historical Society. Also located on the light station grounds are the Maritime Museum in the old fog signal building, the Keweenaw History Museum, the Commercial Fishing Museum, and an exhibit about the 1926 shipwreck of the City of Bangor.

Sand Point Lighthouse

16 Water Plant Road, Escanaba

Located on the same property as the Delta County Historical Museum, this lighthouse was built in 1867 by the National Lighthouse Service. The light warned ships of the dangerous sand reef in the bay. The Sand Point Lighthouse served mariners from 1868 until 1939, except for a few months in 1886, when a suspicious fire damaged the building. The blaze took the life of keeper Mary Terry.

The Sand Point Lighthouse was deactivated in 1939. Nine keepers and their families had lived in the lighthouse and kept the light shining out over Little Bay De Noc during the light’s 71 years of active service. Following deactivation, the building was used by the Coast Guard as a residence for its servicemen. In 1985, the Coast Guard discontinued use of the building. Razing the structure was considered. The Delta County Historical Society stepped in to save one of the oldest and most historic buildings in the area.

A lease from the Coast Guard was negotiated, and research for restoration and fundraising began. The building was completely restored to its original design of the late 1860s, and is now open to the public along with the museum. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

This is one of many lighthouses with a ghost on the premises. Mary Terry was the first lighthouse keeper of the Sand Point Lighthouse. She performed her duties for 18 years, and was one of the first women lighthouse keepers on the Great Lakes.

Mary’s husband, John, was appointed to the position of keeper while the lighthouse was under construction. He died of consumption before the light’s completion, and Mary was officially appointed to take his place. Childless and a widow, she lived alone in the lighthouse and kept the beacon shining during even the worst of winter storms.

In March 1886, fire severely damaged the building and killed Mary. The blaze raised eyebrows in the community, where many people thought Mary had been murdered, robbed, and the lighthouse set on fire to cover the crime.

Speculation was supported by the south lighthouse door found open, the bolt of the door’s lock pushed forward as though the door had been forced open, and Mary’s body discovered in the oil room, rather than her bedroom, which is where she would have been expected to be at that time of night. Mary was a cautious and meticulous woman; one people couldn’t imagine carelessly causing a fire.

An article in the local paper quoted the coroner, “Mrs. Terry came to her death from causes and by means unknown.”

Seul Choix Point Lighthouse

3183 County Road 431, Gulliver

Pronounced locally as SIS-shwa but in true French as SEL-Shwa. The English translation of the name means Last Choice, but it was the only choice for a safe harbor when storms blew across Lake Michigan.

The lighthouse has been in operation since 1895 and is currently automated. Along with the grounds, it is a museum operated by volunteers of the Gulliver Historical Society in cooperation with the Department of Natural Resources.

The two-story, red-brick attached keeper’s house accommodated two families. Several rooms were added to the original structure. The living quarters have been restored and decorated in period furniture from the early 1900s. Visitors can climb the lighthouse tower.

The lighthouse grounds have the original outbuildings, including an explosives storehouse and the fog signal building. An old wood fish net dryer has been moved to the lawn near the house. The fog signal building has been repurposed as a gift shop. The Seul Choix Point Lighthouse is a Michigan Historic Site and a National Historic Landmark.

Lighthouses and ghosts go together as naturally as pasties in a U.P miner’s lunch bucket. Seul Choix remains the haunt of the Joseph Willie Townsend, who was the keeper from 1902 to 1910, when he died in an upstairs bedroom. His death was attributed to consumption, but the diagnosis may not have been precise. Other accounts suggest he succumbed to lung cancer related to his lifelong habit of cigar smoking.

Townsend’s body was prepared for burial. He lay in state in the parlor until his relatives could travel from distances to pay their respects. After his wake, the body was stored in the basement because the frozen ground couldn’t be dug until spring.

What series of events keep Mr. Townsend’s spirit in the century-old lighthouse is uncertain, but many sources and reports swear his ghost refuses to abandon its beloved lighthouse.

Townsend’s wife forbade him to bring his stinking cigars in the house. Today, cigar smoke is often smelled in the house. Maybe Townsend likes the freedom he now has to ignore his wife’s mandate.

Even stranger is current evidence that Townsend continues to express his displeasure with the American way of setting a table. After his death, parts from a kitchen table were found in the basement and taken upstairs and reassembled. More than 100 times, the place settings and the chairs have been disturbed. Forks are turned upside down, placed on the edge of a plate, or formed into a cross with a knife.

There is also the story of a salesman who came to the premises to offer an estimate for installing an alarm system. The man walked through the lighthouse, taking notes as he went. When he left the house, he locked the door behind him and returned to his car where he sat working on the cost proposal he intended to present. He looked back toward the house for a moment and saw Joseph Townsend staring at him from one of the windows. He was so rattled that he started the car, drove away, and let someone else have the job.

Other visitors to the lighthouse have reported seeing Townsend looking at them from a wall mirror.

Don’t let the haunting deter you. Joseph Townsend is a friendly ghost who wants you to enjoy his lighthouse as much as he did.

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies.