Lost Railway Journeys: New Zealand's Otago Central Railway

Note: This is an excerpt about New Zealand's Otago Central Railway from a fantastic new book by Anthony Lambert, called Lost Railways from Around the World. We love it so!

THE OTAGO CENTRAL RAILWAY (OCR) has become far better known since it shut down than it ever was during its working life, because the closed section between Middlemarch and Clyde has become one of the country’s foremost bike routes. Its most southerly section between the junction with the South Island Main Trunk at Wingatui and Middlemarch is today the spectacular 64km (40-mile) Taieri Gorge Railway.

Otago Central trains left from perhaps New Zealand’s grandest station, Dunedin. Designed by the Edinburgh- trained architect and engineer George Troup, the Flemish renaissance-style building was completed in 1904. Its patterned booking-hall floor of almost 750,000 Minton tiles incorporates a locomotive. Photo: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The railway was proposed to link the Central Otago settlements created by the goldrush that was more or less over by 1870. Seven routes into the Otago were surveyed and vigorously debated before work began on the victor in 1879, but it took 12 years to build just 37km (23 miles) to reach Middlemarch. This first section featured some of the longest tunnels and most challenging viaducts on the line, and was built with the help of Chinese labourers made redundant from the gold diggings. The railway became known as ‘the Bridge Line’ for the number and variety of bridge types, the largest being the eight-span 197.5m (648ft) Wingatui Viaduct, which was said to be the biggest viaduct in Australasia when opened by the Premier in 1887. So impressive was the scenery through the gorge that excursion trains began running immediately, though many visitors were also attracted by the engineering prowess of the line.

With the most difficult work done, it was hoped progress would be more rapid, but it proved to be so slow that critics accused the works of being little more than a soup kitchen for the unemployed. Substantial viaducts, deep rock cuttings and more tunnels had to be built at various points where the railway changed river valleys; these were undertaken by contractors, whereas the formation of the line was done under a system of co-operative works in which each man was his own master. Groups of about a dozen workers were formed to undertake and be paid for a specific assignment. Despite periodic deputations to government and protests in newsprint and pamphlets, the remaining sections opened at a leisurely rate, reaching Clyde in 1907 and Cromwell, 236km (147½ miles) from Wingatui, in 1921.

Early travellers in winter may have had mixed feelings about a journey over the line. Any pleasure they may have taken in the varied landscapes of river gorges and upland plateaux offering panoramic views to distant ranges must have been offset by the cold and biting winds of the Otago. Until coaches with steam heating were introduced in 1928, passengers had to make do with sodium acetate foot-warmers – when these hadn’t been chucked into a river by bored schoolchildren. The daily trains from each end of the line made short stops for refreshments at Hindon and Omakau; and there was a longer one for lunch at Ranfurly (previously at Hyde), while trains crossed, crews changed over and the locomotives were serviced. Representatives of Ranfurly’s hotel and two private dining-rooms would meet the train with handbells to attract custom.

A mixed train from Dunedin entering Middlemarch station in February 1911. Both the station and goods shed survive at the southern end of the Otago Central Rail Trail. Photo: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The Hindon refreshment room was originally run by the widow of a construction worker with nine children. Cromwell-bound trains would whistle before entering Ross Tunnel to give her the signal to start pouring the tea; advance warning of Dunedin-bound trains was given by the dog of a member of the station staff who barked as soon it heard the sound of a train rattling over 3 O’Clock Gulch Bridge. A billy can and something to eat would be handed to the crew as their locomotive slowed past the refreshment room. Stops were also made at the lineside for the children of platelayers living in isolated places, though some were taken to school by platelayers’ trolley. Night-time running was avoided whenever possible in the early years because of the risk of rockfalls, though the danger diminished with the decline in rabbits and establishment of lineside vegetation. (Rabbits provided traffic for the railway, carried on special racks in open wagons; as many as 13,000 might be dispatched from Ranfurly in a single day.) Washouts still occurred, notably in 1980 when there were 50 slips between Wingatui and Hindon alone. Snow and ice occasionally closed the line, and in steam days, lineside fires were begun by sparks in the drier months.

A R class 0-6-4T Single Fairlie poses on Christmas Creek bridge with a Dunedin-bound train, c.1890. The 18 Rs were built by the Avonside Engine Co. of Bristol. Photo: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The Otago Central was built to help the economic development of the region – and in carrying its staple traffics of oats and chaff for the horses of Dunedin, fruit, timber, cattle, wool and sheep (as many as 119,736 from Omakau in 1962), it fulfilled expectations. More unusual traffic included pottery clay from Hyde. The railway reduced costs of equipment and fertilizers for farmers and generated enough traffic for two goods trains a day each way, with additional workings during the fruit and stock season (January to April/May). With the deregulation of transport, traffic declined, though construction of the Clyde Dam in 1982–93 brought new flows of cement and steel. The dam flooded part of the line to Cromwell, so Clyde became the new terminus in 1980.

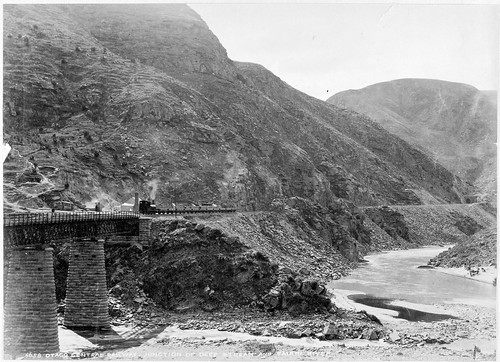

The railway was still under construction when this photograph was taken of a ballast train beside the chimney of a contractor’s workshop, c.1890, where the River Taieri flows into Deep Stream. Photo: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Diesel railcars were introduced in 1956, reducing the journey time from eight hours to a little over five, and the last regular steam train over the line ran in 1968. Excursion trains taking advantage of the line’s scenic attractions became increasingly popular after the Second World War. When New Zealand Railways (NZR) decided to stop running excursion trains in 1976, the NZ Railway and Locomotive Society bought veteran carriages and hired NZR locomotives to haul them, usually as far as Pukerangi. The Society formed the Otago Excursion Train Trust to operate them, and developed evening trains on which a four-course dinner was served during a leisurely journey through the Taieri Gorge.

A daily service was inaugurated in February 1987, using a rake of new coaches with large windows, air conditioning, and catering facilities. Echoing the reliance of today’s TranzAlpine trains on cruise passengers from Port Lyttelton near Christchurch, ‘Cruise Ship Trains’ became important on the Otago Central during the 1990s. Their success was a major factor in the Dunedin City Council taking an option to buy the line as far as Middlemarch when, in December 1989, NZR announced that it would close on 30 April 1990. However, the council called on the community to raise $1 million to fund it; within seven months $1.2 million had been raised, and the line from the Taieri Industrial Estate (4km from Wingatui) to Middlemarch was sub-leased to the Otago Excursion Train Trust following the last train from Clyde.

In common with all long-distance railway lines serving rural communities, the 149 staff (in 1950) employed in various capacities along the line formed a large community, along with their families. Economies to reduce costs gradually reduced staff numbers to less than 20, and it was rural depopulation that prompted a few visionary local people to propose converting the railway between Middlemarch and Clyde into a route primarily for cyclists.

A trust to help with fundraising and promotion was set up by the enlightened Department of Conservation, which bought the line, and it was reopened in stages, with full opening of the Otago Central Rail Trail in 2000. Bridges were re-decked and fitted with handrails, lineside toilets installed, replica gangers’ huts built as shelters with information boards, and the trackbed resurfaced. The 150km (93¾-mile) Trail has become second only to farming in the local economy, attracting about 15,000 a year to complete the whole trail in addition to those on shorter rides. It has been a lifeline for B&Bs, restaurants, cafés, local museums and shops. Railway structures and memorabilia have been left intact or reinstated, and there is a display and film about the railway at the Visitor Centre in Ranfurly station.

Cyclists cross Manuherekia No 1 Bridge in Poolburn Gorge. The Otago Central Rail Trail has become the most popular of New Zealand's long-distance cycle routes, attracting over 12,000 visitors a year and the largest revenue generator in the local economy after farming. Photo: James Jubb

Photos and excerpt used with permission (thank you!).

-

- Log in to post comments