World-famous for adventure travel and cultural voyeurism, Nepal is also a fabulous shopping destination.

By Nepal, I mean particularly Kathmandu and Pokhara. Unlike Singapore and Zurich, Kathmandu and Pokhara are so inexpensive that even travelers who don’t think of themselves as international bargain hunters find that shopping – or at least browsing – is one of the most enjoyable parts of their visit. This is largely due to the long traditions of skilled crafts such as silver and stone jewelry making, wood and alabaster carving, thangka painting, and carpet and pashmina weaving. All are carried on by individuals and small-scale workshops where even the most highly skilled artists and silversmiths earn so little that we are basically paying for raw materials.

An incidental factor that many tourists don’t think about until they are looking for excuses to shop is that the high season for tourism is October and November, shortly before Christmas.

Just for our Wandering Educators, Sunrise Pashmina is offering a 40% discount until Feb. 20, 2021. Click here for the details.

For most tourists, the critical issue soon becomes how to get all the loot back home, especially considering baggage restrictions and Customs issues. (Americans are allowed to bring home only $800 worth of foreign purchases per person.) Bronze statuary, Tibetan carpets, carved furniture, alabaster chess sets, and exotic pets are tempting but challenging. Gifts for children, such as papier mache mobiles, multicolor knit sweaters and caps, and other bargains, may be light and inexpensive, but the value-to-volume ratio is quite low. For many people, the most attractive gift in terms of value, volume, and weight, is pashmina. The main problem is choice: with so much variety and such a wide range of prices, how can a first-time buyer make an informed selection?

Your strategy should be two-pronged: know the product, and understand the market.

About Pashmina

What is pashmina?

The short answer is that pashmina is cashmere. Pashmina is not the best cashmere, or a variety of cashmere. It is just cashmere. In fact, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission does not recognize pashmina as a legal term. Cashmere is the fiber or fabric woven from fiber deriving from the undercoat of certain high-elevation (and therefore long-haired) breeds of Capra hircus, the domestic goat. The fibers are generally 14 to 19 microns in diameter; human hair, by comparison, averages around 100 microns in diameter, while red blood cells are around 7 microns. Some cashmere goat bloodlines have finer and longer hair than others, and the pashmina wool used in Nepal (and elsewhere) varies in quality and price, but the difference is not linked to a terminological distinction known to people in the pashmina trade.

Since many shops in Kathmandu (and online) make a big deal about the “exotic” Capra hircus (or Capra aegragus hirca, or Capra hirca laniger), you should know that this is a distinction without a difference. Capra aegragus is the “Wild goat” from which Capra aegragus hirca (or just Capra hirca) was domesticated. There are about 300 recognized breeds of the domestic goat, of which about twelve are exploited for fiber, including the Angora from which mohair derives. The moniker laniger (wool-bearing) is not a recognized scientific term in caprine nomenclature, although it is used to denote the eastern wooly lemur (Avahi laniger) and the woolly dormouse (Dryomys laniger). As applied to goats, the term is just an affectation.

If pashmina is just the same as cashmere, why isn’t it called cashmere?

A better question would be why cashmere should be called cashmere. The French gave it that name after running across it in Kashmir, in the western Himalayas of India. That’s sort of like calling denim or blue jeans “california.” Pashmina comes from the ancient Farsi (= Persian) word pashm, meaning wool – or, more likely, any weavable yarn, whether deriving from sheep, goat, rabbit, or some kind of plant. It wasn’t very specific.

Pashmina is not the same as shahtoosh (“king’s cloth”), although shawls of either one may be referred to as ring shawls, meaning they can pass through a woman’s ring. Shahtoosh is woven from the wool of the endangered Tibetan antelope (chiru), and is banned worldwide. Nonetheless, production reportedly continues in India, and it is certainly possible to buy toosh shawls, if you have a few thousand dollars to invest in the end of a rather handsome species.

What is a pashmina?

Unfortunately, the word is not used consistently. It may refer to a shawl (generally 28x80 or 36x80 inches), most commonly with fringes, woven of pashmina (goat undercoat) or pashmina mixed with silk. However, the word is also used for anything that looks something like pashmina, whether made of sheep wool, cotton, acrylic, or any other weavable fiber.

Let's be clear: "not pashmina" does not mean "not good." There are lots of gorgeous shawls out there in all sorts of material, natural and man-made, and almost all are cheaper -- way cheaper! -- than pashmina. Recently, shawls made of "modal" have become quite popular... maybe even chic. Modal is a "semi-synthetic" fabric (as opposed to "synthetic," which generally means manufactured out of a petroleum derivative); it is made by chemically mulching plant fiber until the cellulose walls are separated and broken down in little bits that can be reassembled as long fibers. Most modal is apparently derived from beech wood, but the purveyors can safely claim it is bamboo (falsely presumed to be more ecosensitive) because the source of the cellulose is essentially indistinguishable. Modal is robust, soft, and (unlike pashmina) extremely amenable to dyes. These days, India is producing modal shawls with insanely flamboyant digital prints, which look a bit shocking when unfurled, but seem only pleasantly gaudy when draped and folded.

Pashmina unfurled (above) and scrunched (below)

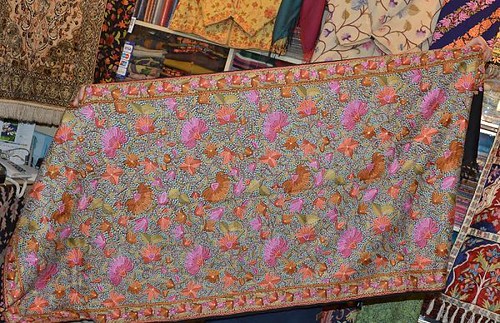

Another non-pashmina fabric worth considering is the fine wool (perhaps combined with a bit of pashmina) that is used as a base for heavily embroidered shawls. The rounded chain-stitching that resembles crochet work is produced with a heavy needle that would pull apart 100% pashmina shawl apart. The fine jaggedy needle point style typical of Kashmiri embroidery can be done on pure pashmina, but is usually done on sheep wool. Real Kashmiri-style embroidery always leaves a rat's-nest of threads on the back side; embroidery done on a sewing machine looks quite similar on both sides. Again, the machine stitching (which is actually applied by hand, not by robot) may look better, but connoisseurs prefer the much more labor-intensive hand-stitched variety.

Full surface embroidery is Kashmiri "jamawar" ... on sheep wool, not cashmere. Still, many of these pieces are gorgeous works of art, and extremely good buys, even if they are imported from Kashmir, in northwestern India. (The shopkeepers are usually Kashmiris; they produce the shawls in their own workshops, and import them to Nepal without paying any kind of customs duty -- which is to say that you can expect the prices to be more or less comparable in Kathmandu to what you’d pay in India.)

What is the difference between pashmina and chyangra pashmina?

None. After years of litigation, Kashmir pashmina was designated a “geographical indication” for cashmere coming from Jammu-Kashmir in India, according to the terms of the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement of the World Trade Organisation; Nepal settled for chyangra pashmina. Chyangra means goat in Nepali. There is no substantive distinction, no quality control, and no enforcement. Most Nepalese producers correctly identify the hallmark issue as a marketing tool of the recently established lobbying group, Nepal Pashmina Industries Association. In fact, virtually all pashmina yarn used in Nepal manufacturing is produced in China; the same is probably true of Indian cashmere, as Indian goat herds have been greatly reduced by blizzards in the last 20 years.

Is two-ply better than single-ply? Or vice versa? What about three-ply?

Ply, in the context of woven goods, refers to the structure of the yarn. Single-ply yarns are spun as a single thread; double-ply or two-ply yarns are made by twisting two threads together. Multiple plies may be used to produce a heavier cloth, especially in knitting, but in weaving there are other pertinent factors: the weight of individual threads can be varied; and the loom can be adjusted to produce a tighter or looser weave. So it is not necessarily true that a higher number of plies makes for a heavier fabric. But there is a prior question: do you really want a heavy shawl? The great advantage of pashmina over most other fabrics is that the fiber is rather kinky at the microscopic level, which means that it traps air better than straight-shafted hairs, and also that it tends to recover its original shape after (limited) stretching. For centuries, pashmina has been treasured for its unusual combination of warmth and lightness. If the shawl is being worn instead of a parka in frigid conditions, a heavier shawl might be desirable – but a parka could actually be a better choice.

Why is pashmina blended often with silk and what proportion is best?

Pashmina/silk blends can be found in 50/50, 70/30, and 80/20 proportions. Silk is more rugged than most natural fibers, including pashmina and sheep wool. It is also more dense, which means that it drapes better, and it has a sheen, which may be desirable. On the other hand, silk is naturally unkinky at the microscopic level, and is not going to add much to the insulating quality of the fabric. Until the last few years, silk was quite a bit cheaper than pashmina in Nepal, so the blended shawl was heavier, stronger, cheaper, shinier, and less warm in proportion to the amount of silk in the blend. These days silk is just as pricey as cashmere, so more people are opting for 100% pashmina shawls.

Pashmina is sometimes blended with other fibers, notably cotton and sheep wool, for one of two reasons. First, the admixtures make it cheaper. Second, as mentioned above, the stronger sheep wool -- like the silk -- can safely be embroidered, while pure pashmina is more likely to be damaged in the process.

What size pashmina should you buy?

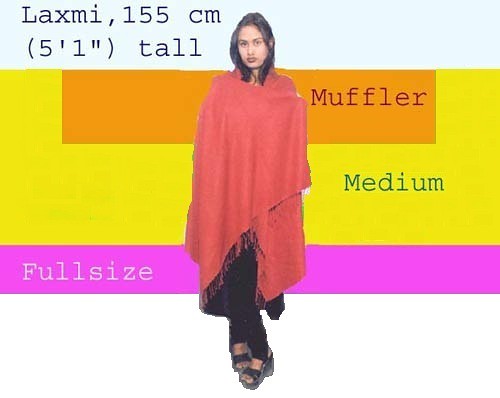

The full-size shawl is 36x80 inches, which may seem gigantic, especially for a petite woman. It’s not. Nepalese women are generally quite small, and the traditional dimensions evolved to suit them. The superlight fabric is ordinarily twisted, folded, and pleated, giving it extra warmth and remarkable versatility.

In Nepal and India, pashmina sizes are generally referred to by English words that don’t necessarily match usage in the language-at-large. Shawl is the standard 36x80 inch wrap; stole is 28x80 inches; scarf is 24 or 22 inches wide, and usually about 72 inches long; a muffler is normally about 12x72 inches. Of late, the stole size has become more popular than the full shawl, apparently because shopkeepers are competing for cost-conscious Chinese tourists.

There are quite a few weaving styles available

For years, the most common weave for 100% pashmina was a rather gauzy plain basket weave – up and down in a checker-board pattern. Twills are produced by jogging the horizontal weft threads, producing diagonal ridges; typically, these are heftier fabrics than the basic weave, and the reduced number of contact points between weft and warp is said to allow the yarn to slide a bit and improve drape.

Herringbone and other jacquards have become more popular as well; the chashm-e-bulbul (Urdu for “eye of the bulbul [bird]” also known as diamond weave) is gaining popularity, especially as applied to the superfine 120/count weave.

For the most part, weave is a matter of visual appeal, but the denser twills are warmer and drape more elegantly than the lighter weaves. The lighter weaves, on the other hand, are more versatile: the fullsize superfine diamond weave, for example, can be worn over torso and head, as a sort of hoodie, or bunched up and worn as a sash or a cravat.

Pure pashmina: twill (left) vs plain weave (right)

Superfine 100% pashmina in "chasm-e-bulbul" diamond weave

The plain weave in 100% pashmina appears especially gauzy when photographed with flash; the shawls are not at all see-through when worn under normal lighting conditions, especially when draped in overlapping folds.

Fringes? Really?

The 3-inch twisted and knotted tassel has come to be seen as an identifying feature of pashmina shawls. There are variants – beaded, latticed, or variable-length fringes. Hemming is also possible. These days, more shawls are being sold with “ragged fringe” (aka eyelash); woven pashmina, unlike knit fabric, tends not to unravel when broken. Regular tassels tend to look wispy on lighter pashmina weaves, so most superfine shawls are available only with eyelash fringe.

Nepalese embroidery on 70-30 pashmina silk

What are the determinants of quality?

Color-fast dye is important. There are Indian dyes and Swiss dyes in use, and the Indian are reputed to be less stable than the Swiss. When shopping, you could wet a corner of a handkerchief and squeeze it on the pashmina to see if there is a color transfer. (Ask the shopkeeper first.) There may or may not be genuine vegetable dyes on the market these days, but they certainly are not common. Natural (undyed) pashmina comes in a range of grays, cream, and brown.

You can also test for non-pashmina content by burning a single fiber; if it forms a black ball, it’s probably got some synthetic content. Pashmina will reduce to a schmeary powder, with a typical burnt-hair odor, and a hint of goat. You can check for shedding or rub the surface lightly to see if it pills up immediately – that would be a sign that the fibers are too short. However, all cashmere can pill (and shed), if the fabric is repeatedly scuffed or rubbed – for instance, by wearing it under a coat.

What about that smell?

Pashmina has a natural lanolin oil that goats find appealing. Usually that smell is masked by the chemicals in the softener and dyes, but it may persist for a few wearings. If it bugs you, just hang it outside and let it air. If the shawl has local embroidery, let it air.

Sometime the issue is a smell like jet fuel. That seems to happen only with locally embroidered shawls (as opposed to those imported from Kashmir). That's because the embroider uses a sketch drawn on the shawl with soap to guide the needlepoint, and then washes it away with a petroleum product. If the shawl is not aired properly (which can happen during the rainy season), it may be packed for sale before the smell dissipates. No big deal. You can air it out as easily as the dyer should have.

Pashmina goats

Hand-loomed or power-loomed? Can you even tell the difference?

All pashminas are loomed on big clunky machines. The issue is, does a human shove the shuttle by hand to lay the horizontal weft yarn row by row, or does it all happen automatically?

There are two differences in the product.

Power-loomed fabrics are perfectly regular. The edges of the shawl have essentially no wobble. Hand-loomed fabrics may be quite regular, but you can always find departures: wobbles, unequal spacing, even repaired yarn breaks. Pashmina connoisseurs, like carpet connoisseurs, value those slight imperfections as “personality” – the signs of a human craft. Another difference, especially with respect to 100% pashmina weave, is that hand-loomed fabrics can be tighter than power-loomed. Because the yarn is relatively fragile, there is always a chance of its breaking under tension. Since a break causes a costly disruption of production when a power-loom is at work, the warp yarns are strung under less tension than is typically applied on a hand-loom. Less tension on the loom produces a less dense (less fine) fabric.

So: power-loomed fabrics may appear more perfect, but they are less desirable. Of course, most large-scale purveyors of pashminas must rely on power looms, since they are dealing with more stringent production schedules.

What about softness?

This is a squirmy topic. Part of the problem is that cashmere has a reputation for preternatural softness. To impress our uneducated fingers, pashmina producers resort to chemical softeners, which probably don’t hurt the cloth (although they may make it smelly or otherwise allergenic), but certainly aren’t necessary: pashmina naturally softens up with use, just as blue jeans do. But there are worse palliatives. The first pashmina I ever bought, for my then girlfriend’s mother, was extremely soft and fuzzy, and I didn’t learn until years later that this was due to brushing. The surface of the shawl is literally ripped up, as if your cat were allowed to have her way with it. Needless to say, my girlfriend subsequently dumped me, although the shawl was never admitted to be a proximate cause.

Pashmina is quite buttery and spongy, but whether you will recognize that special quality may depend on your familiarity with fabrics. Guys don’t seem to pay much attention to such things, so if you are buying pashmina for someone with more astute fingers, you may have to develop a workaround. For instance, spend some time in a reputable upscale store prior to leaving for Nepal, and finger cashmere and woolen garments until you are more familiar with the distinction between them. Or … shop with a female companion who won’t spoil the surprise.

The Marketplace

Things called pashmina are sold on the street, in small shops, and in upscale boutiques. Generally speaking, you may find attractive shawls in all those places, but you’re not going to find authentic pashmina in the cheapest venues, anymore than you’ll find Cartier watches in Walmart. If you want a top quality pashmina, you should shop in an area frequented by tourists: Thamel, Durbar Square, or in and around the fancy hotels such as Annapurna and Yak and Yeti. For the most part, those stores will only sell pashmina – no curios or other handicrafts.

Two factors make shopping a challenge in Kathmandu (and elsewhere in developing countries): the prevalence of counterfeit goods and the rarity of fixed prices.

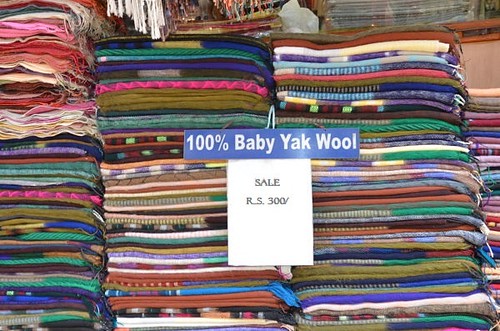

To be clear: labeling and signage are never guarantors of anything in Nepal. No one gets prosecuted for commercial fraud. Knock-offs of North Face, Marmot, and Mountain Hardwear are sold openly; sales assistants will readily admit that the stuff is fake. Labels claiming “100% pashmina” are often aspirational. In most cases, the shopkeeper or salesperson will have little direct knowledge of the yarn composition, since it is bought from China, where fraud is also rampant. Any place that advertises bargain-priced "Yak wool" or "Baby Yak Wool" goods is going to be a bad bet, since yak wool is just not used on a commercial scale. You can pick up yak blankets in Tibet, and I bought some in Namche Bazar years ago, but there is not enough yak wool in Nepal to supply all those shops that claim to sell it. Any fabrics displayed outside in piles must be something cheaper than real pashmina, never mind yak.

Serious pashmina purveyors will have their wares on shelves, protected by clear plastic sleeves.

Speaking of labeling: most will say "dryclean only." Actually, you're better off handwashing with pure soap in warm water.

300 rupees (about $3) for a yak wool shawl?? Not likely!

Places that sell “water pashmina” should also be approached with skepticism. “Water pashmina” is just a come-on for ignorant tourists: the fabric is invariably a shiny synthetic that has nothing to do with goats. The same goes for places that display photographs of the supposed “pashmina goat” that are actually the [North American] Rocky Mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus): avoid them.

"water pashmina" - avoid

Pashmina? Not with that goat.

Don't buy this sweater if you want real pashmina

The fact is that most pashmina salespeople do not have good first-hand knowledge of the manufacture or sourcing of their wares.

What about pricing?

Even those places that post “fixed price only” signs will probably give a discount of five or ten percent to close a deal. But in many shops, especially smaller ones catering to the uniformed, the suggested “tourist price” may be much higher than the “local price.”

This shop in the heart of Thamel is owned by Pranab Manandhar, who supplies our online company, Sunrise Pashmina. If you go there, tell him that you're looking for the same quality and price that he gives us. He has a range of qualities in pashmina, as well as modal, silk, and other fabrics, and he is happy to explain the differences.

Here are my suggestions for not getting rolled:

1) Don’t wander into a store where you are the only prospective shopper. Above all, don’t let a salesperson start unfurling shawl after shawl for you: it’s very hard to walk out without buying anything, leaving the mess to be cleaned up by the eager shopkeeper. Instead, draft behind a cluster of other shoppers, and observe carefully. Leave without purchasing. Walk past the store, and look at window displays, several times over a period of days. The shopkeeper will recognize you as a cautious (and perhaps savvy) shopper.

2) Come prepared with a story. I usually say I’m just looking on behalf of my wife, who will have to stop by and make a decision later on. Or I say that I am totally ignorant, looking to start an export business, and need information. I ask what goods (size, weave, color, quality) are preferred by diverse customers: Americans, Europeans, and Chinese, for example. Then I ask detailed questions about quality and pricing, and keep pressing to see more expensive goods, and trying to pin down the quality factors that impact pricing. If I see any signs that the sauji (shopkeeper) doubts my story, I follow up with inquiries as to minimum order quantities, quantity discount, production time, delivery cost, and manner and timing of payment. I will ask where the factory is located and if I can visit it. Finally, if I really want to purchase, I will ask for the sample policy. That should get us pretty close to the minimum acceptable price.

While it may seem disingenuous to pose as a potential business partner, the truth is that a lot of people set out to shop for themselves or their wives and end up actually going into business. We recommend it; let us know if you want advice.

There is an epigram attributed to Bion of Borysthenes to the effect that the boys throw rocks in jest, but the frogs die in earnest. As recreational shoppers, we tourists are making choices of substantial import to the shopkeepers: losing a sale is painful. Most Nepalese shopkeepers are friendly, and genuinely enjoy talking to foreigners. As far as they’re concerned, there is no adversarial relationship. Let’s try to keep it that way.

Happy shopping!

Seth Sicroff is the Nepal Editor for Wandering Educators, He and his wife Empar (shown in some of the above photos) have owned Sunrise-Pashmina.com since 1999. Their Web site has comprehensive information on the laundering and styling of pashmina shawls. Seth is also director of the Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Medal project of Mountain Legacy (www.hillarymedal.com; www.mountainlegacy.org); the prize is presented more or less annually "for remarkable service in the conservation of culture and nature in mountainous regions." If you know (or are yourself) a worthy candidate, please email Seth at sicroff[at]hillarymedal.com.

All photos courtesy and copyright Sunrise Pashmina/Seth Sicroff, except:

Pashmina Goats. Photo Wikimedia Commons: Redtigerxyz

Word photo: Wikimedia Commons: Tom

Note: this article was originally published in 2017 and updated in 2021.