In a quiet room, a nameless English poet gazed at his work for a moment. A faint smile crossed his face, and he nodded once before carefully wiping his quill and putting it away. His work was complete for the day, and he was satisfied. On the parchment beneath his ink-stained fingers, his quill had carefully scratched a masterpiece into existence:

Remember, remember!

The fifth of November,

The Gunpowder treason and plot;

I know of no reason

Why the Gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

Guy Fawkes and his companions

Did the scheme contrive,

To blow the King and Parliament

All up alive.

Threescore barrels, laid below,

To prove old England's overthrow.

But, by God's providence, him they catch,

With a dark lantern, lighting a match!

A stick and a stake

For King James's sake!

If you won't give me one,

I'll take two,

The better for me,

And the worse for you.

A rope, a rope, to hang the Pope,

A penn'orth of cheese to choke him.

A pint of beer to wash it down,

And a jolly good fire to burn him.

Holloa, boys! holloa, boys! Make the bells ring!

Holloa, boys! holloa boys! God save the King!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To others, Westminster Palace was a marvel; a masterpiece of modern architecture. A sign that in the year of our Lord, 1606 Anno Domini, civilized man was capable of wonders. In the daylight, when all evils shrink into the shadows, some said it glowed with promise and beauty. But in the stifling gloom of a London night, it loomed above me - dark, somber... ominous. How we hated it. To others, it was simply an impressive building, soon to house King and Parliament. But to the Twelve, however, Westminster Palace had become more than that. To us, it was a symbol of the utter dominance of the monarchy, an ever-present reminder of the daily oppression we endured. It mocked us by day, taunted us by night, ceaselessly reminding us of King James I, his power, and his vendetta against us, the Catholics.

I gazed up at the palace for a moment longer, and smiled grimly. It would not mock for much longer. I spun, wrapping my cape more closely around my shoulders, and made for the Duck & Drake. Thick fog swirled around my ankles as I walked; my boots thudded softly against the cobblestone streets. The inky blackness that enveloped the less frequented back roads of the city was as cold as ice. Like cracks in London’s carefully polished veneer, the alleyways stretched throughout the city, creating a maze I had learned to love. On this night, like so many before it, the grimy alleyways were quiet. Here and there, a drunk or beggar curled into a doorway, rags wrapped tightly around their bony forms. I navigated around them with ease, passing like a shadow along the pathways I knew so well. Except for the occasional bark of a suspicious feral dog, silence reigned. At last, I left the dark shadows of the alleyways and came out upon a busy street. Music seeped from beneath the doors of multiple taverns and inns, mingling with the overpowering smell of ale and sweat. The stink lay in the street, a nauseating monster that rose up to attack me. But nothing would stop me on this night: tonight, I would become the Thirteenth.

The sign above the inn door was old, and poorly painted. A brown duck nested beside a river, more gray than blue, while a drake reared proudly above her. His beak had faded, and where the paint had curled back, his feathers were dark and ugly. The Duck and Drake. One of the least conspicuous meeting places in all of the Strand. With a shove, the door creaked open, and I stepped into the inn.

It was a busy night - a good sign. We were less likely to be overheard. In the corner, a musician in a threadbare overcoat picked out a tune on a worn clavichord. Businessmen leaned back in their chairs confidently, each working to strike a deal that would leave himself better off than his opponents. Friends laughed together. Travelers washed the dust from their mouths with poorly seasoned food and beer that had, no doubt, been watered down by the innkeeper. And, in a dark corner, revolutionists conspired. They were there, in the shadows. Unnoticed by the mob of humanity surrounding them, five of the Twelve had gathered around a worn wooden table to discuss the fate of Great Britain. My heart beat a drum roll as I approached them. It’d taken me months to arrange this meeting. I’d chased names, made both threats and promises, and spent what little savings I had in order to ensure that this moment would come. Silently, I prayed that all would go as planned.

Robert Catesby rose to meet me. “Greetings, Fitch! I must say, my lad, it’s good to see you again.”

I inclined my head respectfully. “Catesby, how can I thank you enough?”

He chuckled, and turned to the others. “Gentlemen, allow me to introduce Fitch Blackwell, the thirteenth to join our business venture.”

As they stared at me in silence, my skin crawled uncomfortably. I was all too well aware of how I looked to them. A young man, not yet thirty, dressed in a second hand doublet and boots so worn I expected holes to appear in them any day. I looked ragged and desperate, and I was well aware of it.

“How do we know that you will prove to be a... productive member of our venture?” The voice was harsh, calculating. Five pairs of dark eyes bored, it seemed, into my very soul. I glared stubbornly back.

Slowly, deliberately, I leaned forward, placing my palms against the worn boards of the table. My voice rasped hoarsely when I spoke, and the five leaned close. “Gentlemen, my father was imprisoned when I was a boy, not for murder or theft, but for recusancy.” A painful lump, cold as ice, slid up my throat to choke me. “He died there, the cold walls of the prison cell closing in around him. His Highness, King James |, killed him for refusing to attend an Anglican service. My mother raised me Catholic anyway.” I looked each of them in the eye. “I believe in a world where free speech should be granted to every British citizen, and no one should have to hide their religion for fear of persecution. And I’m willing to die for that belief.”

A low voice, more powerful than a thousand thunderstorms, rolled from the shadows. “Be at ease, my companions. Would you deny a fellow sufferer the comfort of conspiracy?” The man came into the light. His eyes burned with power, with an idea - an idea that had infected us all, and had inspired us to band together and fight back.

Guy Fawkes smiled, and reached for his mug of ale. “I would trust young Blackwell with my life.”

The Thirteenth. I was the Thirteenth.

Guy Fawkes, 1606, by Crispijn van de Passe der Ältere (1564-1637). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Inky blackness swirled coldly around me. I held a bundle in my hand. Its weight was familiar and reassuring. It wasn’t the first time Guy and I had made this trip to the cellars. I knew the corridors like the back of my hand, and unless something had been moved, I would not be lost.

There was a dull thud. I listened intently. That would be Guy, closing the doors behind us. The darkness retreated as he made his way between the cold stone walls to me, holding a lantern before him. He nodded, and I fell in behind him silently. The air was chill, and damp. Guy cursed it vehemently. “The damp will be our ruin, Fitch. God save us if it gets in the powder.”

We reached the end of our path. Fawkes passed me the lantern. “Hold it carefully now,” he muttered, gazing up at the stack of cordwood. He grinned. “We wouldn’t want to begin too early, would we?” He reached up, pulling away the topmost bundles of wood, revealing a barrel. His face shone with anticipation. “Threescore barrels of powder. Smuggled here, beneath Westminster Palace. And tomorrow, when King and Parliament unite to rule from their newly constructed throne... we will destroy them, and all they stand for, Fitch, now and forever. With the good King’s young daughter installed as the Catholic Head of State, our troubles will end.”

Was it the right way, I asked myself? We would murder hundreds, place a girl of nine years on the English throne, and risk our lives, all for the sake of an idea. It was a grim prospect. But there is nothing more powerful than an idea, and we would do anything for freedom.

Guy and I grasped each others hands firmly. “Tomorrow,” he said.

“Tomorrow,” I promised, and clutched my bundle of matches close.

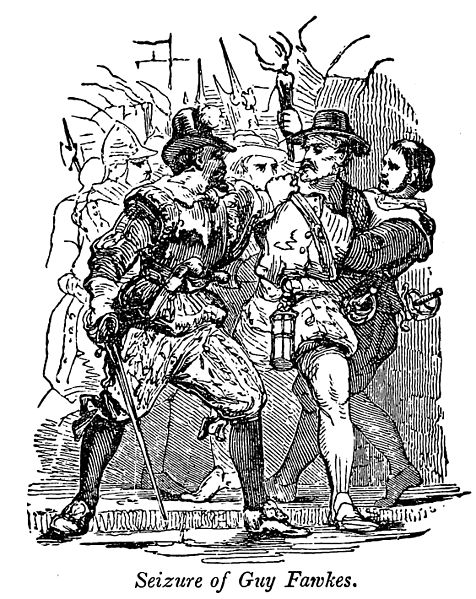

They came in the night, as we guarded the powder.

As the shouts of the soldiers rang through the corridors, Fawkes turned to me, his face grim. “You must warn the others, immediately. Their survival depends on you. Take the back passageway, Fitch, and may God go with you!” With that, he shoved me into the shadows, pulled a sword from its hiding place, and waited by the door, jaw set and eyes burning. I ran, hating myself for it, wanting to stand with him, but knowing that a reckless act of valor wouldn’t save the others. I pounded through the corridor, up a slimy set of stairs, through a wooden door, and out into a grimy London alley.

The seizure of Guy Fawkes as depicted in the book "A Pictorial History of England" (1854). Samuel G. Goodrich (1793–1860). Wikimedia Commons

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A crowd had gathered. Men, women, and children surrounded the gallows, booing and hissing. A grimy young boy ran past me, clutching two rotten tomatoes in his fists and hooting with laughter. He disappeared a moment later, squeezing between the forest of boots and skirts towards the platform. A noose swung limply in the breeze, and the executioner stood waiting at his post. But for whom? A murderer? A conspirator? I tapped the shoulder of a man who stood howling with bloodlust nearby. He turned, his eyes fierce and wild. “Aye?” he demanded hoarsely. “Who is to be executed?” I shouted. He cupped a coarse hand to his ear, straining to pick up my words over the wailing crowd. “A traitor!” he shouted back, “of the highest degree, they say.” I shuddered. Traitors were not allowed a quick and merciful ending. They were hung, cut down before dead, and then castrated, disemboweled, and quartered while fully conscious. The hissing and booing became louder, more frantic. I strained to see the traitor. Who was he?

I gasped, suddenly unable to breathe. The man was utterly broken. His flesh had melted away, leaving bones and a scant bit of skin to cover them. But his eyes, I knew. Although they had sunken into his skull, they still burned with fierce determination and belief. As I watched him slowly climb the ladder to the gallows, his voice rang in my ears. “I would trust young Blackwell with my life.”

I had failed him. He went to his death, the leader of one of England’s greatest conspiracies, and I, his assistant, his friend, went free. I should have felt some emotion. Pain? Guilt? Anger? But I was numb, void of all emotion but shock.

Guy scanned the crowd for a moment. I feared that he would see me, yet I feared that he would not. His eyes passed over me without any sign of recognition, then closed slowly. With a grimace of determination, Fawkes threw himself from the top of the ladder to the ground below, diving headfirst towards the stone. I bowed my head, and as the crowd shrieked with rage at the deprivation of their proper execution, a blinding white light encompassed me.

The Thirteen had been betrayed by one of our own (who exactly, we’d never know), our plot torn to pieces by King James’s guards. Westminster Palace stood untouched, the King safe upon his throne. One by one, seven of the Thirteen were tortured, tried, found guilty, and executed. The Catholics would remain in a state of oppression. Was it all for nothing then, I wondered?

The execution of Guy Fawkes' (Guy Fawkes), by Claes (Nicolaes) Jansz Visscher, given to the National Portrait Gallery, London in 1916. National Portrait Gallery, London. Latin Text Translation: The PUNISHMENT. exacted from the eight conspirators in Britain, on January 30 & 31 Old Style, 1606, actually exacted in separate groups of four, but nevertheless on account of the very same cause of Punishment.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

My eyes opened slowly. I lay in bed for a moment, too disoriented to want to move, or think much. The light fell in through my bedroom window, casting the oddest shadows on the floor where the fan moved the curtains. The digital interface of my alarm clock blinked, glowed red, and blinked again. Was it really already nine thirty? More importantly, where was I?

“Fitch! Get up already!”

It was... my mom? For a moment, utter confusion reigned. I was Fitch Blackwell! I was the Thirteenth, and I had just survived the famous Gunpowder Plot of the 1600’s! But I was also Fitch Smith, a sixteen-year-old in New England, who had just barely survived yesterday’s history exam.

I groaned, and forced myself to shed my blankets and return to everyday life in the 21st century. And, not for the first time, I thought about how lucky I was. For unlike Guy Fawkes and the other conspirators of the Gunpowder Plot, I had freedom of speech and freedom of religion.

Although Guy Fawkes and his companions failed in their plot to blow up Parliament, their sacrifice opened the eyes of many who went on to make significant changes in the way Catholics were treated. Because the event was so noteworthy, a poet whose name has been lost to history, captured it in words, which spread like fire around the world. Words, and hence ideas, are the most potent weapon any revolutionist or dreamer might utilize. And though those who create them may never be remembered by name, they will live on for centuries after death through the inspiration they bring to others. Without their sacrifices, and the sacrifices of hundreds of thousands of others like them over time, the world would be a very different (and not necessarily better) place today. Interestingly enough, even the words that railed against the people’s heroes seemed only to make them even more popular. I shook my head as I left the room. It was a strange place, this world.

The Gunpowder Conspirators are discovered and Guy Fawkes is caught in the cellar of the Houses of Parliament with the explosives. 19th c wood engraving, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Hannah Miller was a member of the Youth Travel Blogging Mentorship Program. Find her online at http://www.edventuregirl.com/

This article was originally published in 2013 and updated in 2017