The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan's Coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

The Niagara went down on September 24, 1856. She was built in 1846, and during her decade of sailing, she earned a legacy that would endure after her demise. She brought thousands of German and Scandinavian immigrants from Canada and New York to start new lives in Wisconsin and Michigan. She was one of the strongest and most powerful ships built in the mid-1800s. As her strength sapped the night she sank, she witnessed heroism; she witnessed evil; and she witnessed rank, unmitigated terror.

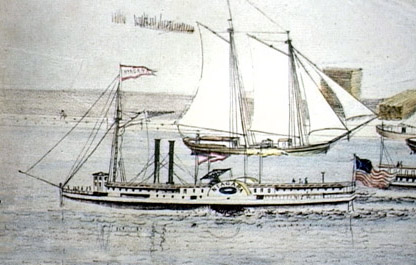

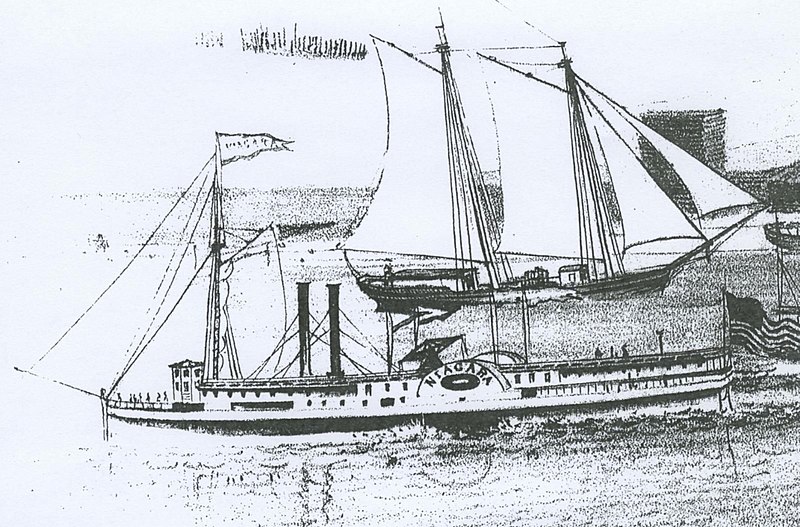

A drawing of the Palace Steamer, Niagara. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Niagara left Sheboygan, Wisconsin, bound for Chicago with 100 cabin and nearly 200 steerage passengers aboard. Captain Fred S. Miller, expecting a calm and uneventful trip, grabbed a quick afternoon nap. He was awakened by screams of “Fire!” A cloud of black smoke and blazing flames rose from the engine room. Captain Miller wasted no time getting the fire hose in position, and the engineer began to douse the flames. The captain rushed to the pilothouse and ordered the ship turned toward shore. Within a few minutes, the engine had stopped, and the burning ship foundered—safety a short distance away.

It was not uncommon in the mid-1800s for a ship to lack life preservers, so the frantic Captain, assisted by several passengers, began pulling down stateroom doors and pitching them into the lake along with gangplanks, chairs, washstands, and anything else that looked likely to float. They had only a few minutes to accomplish these last-ditch efforts before the center portion of the boat was engulfed in flames. Most of the crew was trapped forward with no movement possible between the stern and the bow.

Mishaps with lifeboats may have been the single largest cause of death from the disaster. Fear-crazed passengers attempted to launch lifeboats on their own. The largest of the lifeboats capsized upon hitting water.

Acts of courage and cowardice commingled that night. One lifeboat, safely lowered into the water with women and children aboard, was rushed by a group of men who jumped into it from the deck above. The flimsy lifeboat flipped, sending all but four of its occupants to the depths of Lake Michigan.

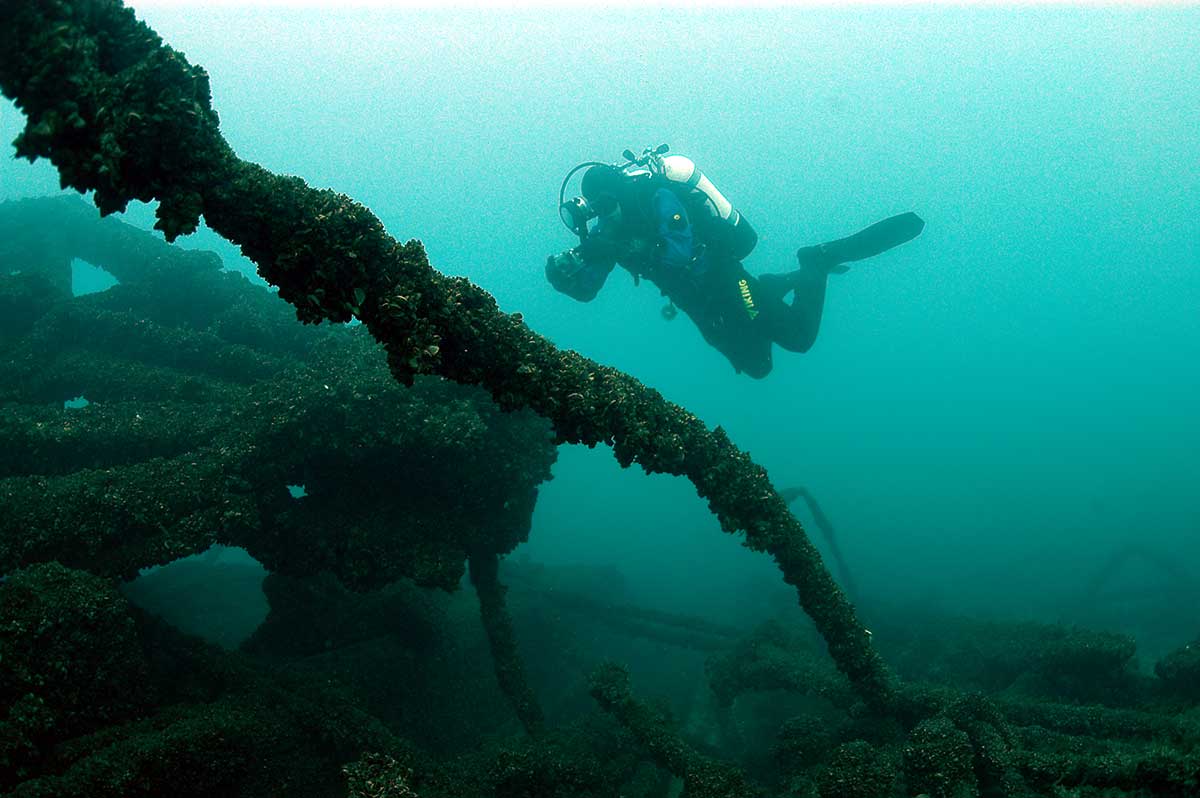

An archaeologist photographs the remains of the paddle-wheel. Photo by WHS, Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program, via Wisconsin Shipwrecks

An even more despicable act of cowardice was attributed to former Wisconsin congressman, John B. Macy, who in his better days was described as a brave man with a cool head. Perhaps the scenes he witnessed that night addled his normally clear brain. Macy, a rather portly gentleman who could not swim, is said to have screamed, “Oh, God, someone save me. Ten thousand—a hundred thousand to the man who will save my life.” Getting no takers, he spotted a lifeboat filled with women and children being lowered into the water; one end was lower than the other. He jumped, and his prodigious weight caused the ropes to break, casting everyone inside the unbalanced life craft to a watery grave. The ex-congressman was never seen again.

Standing at the railing next to Macy, when the congressman made his ignoble offer of reward, was a tiny lad, maybe two years old. His parents were nowhere in sight. A deckhand ignored Macy’s pleas but picked up the child and jumped into the water clutching the toddler tightly. The deckhand grabbed a piece of floating gangplank and courageously paddled them toward shore. By the next morning, the two were found where they had drifted onto the beach. Both lived, but the deckhand left town, and his name was never known. He remains the anonymous hero of the tragedy.

The child was taken in by a couple in the area and identified as Frank Willette, the name on a small gold cross that hung from his neck. His new caretakers advertised in newspapers throughout the country, but no one claimed the child. Several decades passed and the young man, who went by the name of Frank Willis, made his own attempt to locate family by running ads similar to those run many years earlier. Defying all odds, he was contacted by an aunt residing in Nebraska and a cousin in Manitowoc. They confirmed his real name was Frank Willette, as had been engraved on his cross. His parents, a brother, and a sister had died in the Niagara tragedy.

One of Niagara's paddle-wheels and drive shaft extending from the wreckage of the hull. Photo by WHS, Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program, via Wisconsin Shipwrecks

On the evening of September 24, with safety only a mile or so away, and beaches clearly in sight of those slipping under water for the last time, at least 150 either drowned or burned. If that is not a sad enough ending to this story, there was also speculation that the fire was intentionally set.

On a previous trip, just after the ship left port, a steward found a note on the table in his room: “Look out. Save yourself. The boat will be burned tonight. Everything is in readiness.” Had a crazy person sent the note and then lacked the courage to carry out the threat until the next trip? Some questions will never be answered.

Lithograph of the paddle steamer Niagara. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies. All books available on Amazon.

Help promote Michigan. Books available on Amazon.