In colonial times, the military usually took the best spots of settlement, you know, security and all that, although Governors and their ilk generally didn’t fare too badly, either. On the tops of hills where in the days before planes, you could see the enemy coming, by ship, foot or horse, there were often forts with tunnels to gun-ports. Sometimes authorities declared whole islands and headlands “strategic,” keeping them only for themselves. Well, one of the ‘joys’ of greater use of sophisticated weaponry in the last eighty years has been the “peace dividend” of virtually obsolescent forts. Consequently there has been public clamour for defence land to be opened to the public as parkland for the preservation of facilities of historical importance. And being a harbour city, Sydney has such places in abundance. What is more, most of them are now Heritage listed, offer superb views, and are either free to admission, or for the payment of a nominal fee.

Which brings me to Cockatoo Island, World Heritage listed for its convict history (1839 - 1850, although convicts worked there till 1870 building a dock to service Royal Navy ships) and industrial architecture. Some of the most recalcitrant cons were sent there to build their own prison, barracks, a guard-house, and of course “offcial residences,” with the obligatory harbour views. Few convicts could swim (they were Poms after all, and this was well before the London Olympics!) and the waters were claimed to be “shark infested.” Only one con is recorded as leaving without a “Ticket of Leave,” one Fred Ward, who was left cell breakout tools in the shoreline bushes by his devoted part-Aboriginal wife, Mary Bugg, over on a ‘spousal visit.’ One night in September, 1863, together with a convict mate, Fred made a swim for it. The mate drowned but Fred found the distant shore, Mary, and a speedy white steed. He “went bush” to Northern New South Wales where as the more aptly named Captain Thunderbolt, he became a notorious bushranger (outlaw), till the wallopers (police) caught up with him in 1870 and “boom,” - no more Thunderbolt.

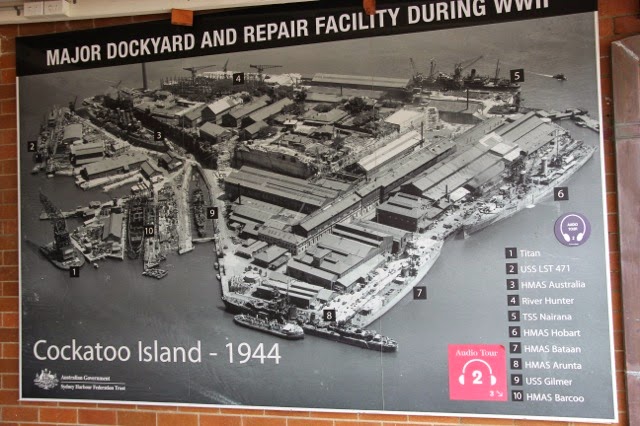

After serving as the site of an “industrial school for girls” and a Reformatory for “wayward and orphaned boys” on an off-island hulk, the whole island became a Government shipyard, given to repairing and victualing ships. In 1901 it was taken over by the newly founded Australian Government, for the building and repairing of steel ships. During WWII, following the fall of Singapore, it became the key dockyard facility for the whole South West Paciic war effort. Between 1965 until its closure in 1992, it was used to construct Australian warships, service and repair submarines. It was taken over by the Sydney Harbour Trust in 2001 for ‘rehabilitation,’ and opened to the public in 2005. As always, it remains a short, scenic, 20 minute fabulous ferry boat from Circular Quay, in the heart of commercial Sydney and is simply a visit must for its views and industrial architecture … and if you wish it, for its camping or glamping.

Approaching Cockatoo Island

On a blustery day, when the wind was sailor keen, I caught the ferry Marjorie Jackson (named after the Lithgow Flash who had won 3 gold medals at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics), to Cockatoo Island, named after the large number of sulpher-crested white cockatoos which once lived there in number. A very helpful lady met our group of land-lubbers, explained the island lay-out and offered a very well designed Sydney Harbour Federation Trust booklet, for a gold-coin donation ($A1 or 2). I loped off for a latte and began to read, glancing up occasionally at the stupendous Sydney skyline, the bobble of its famous Bridge above islands, water, bushland, yachts, and houses which filled my canvas to the tall buildings. Sippingly sated, I shuffled off towards the camp-ground beside the harbour waters, tidy as though painted, quiet with the still sleeping, munificent in its setting on this morrow.

Camping came with BYO 4X4 metre sites at $45 per night or in pre-erected tents, with mattresses and chairs, for two adults and two children at $89 per night or “Glamping” for the “comfy crowd,” with pre-erected tents, camp beds, linen, sun lounges, an Esky (beer fridge) and a lantern, at $150 per night. Toilets and spotless ablution blocks meters away. An Island Bar nearby, with strict noise observance hours, two licenced cafes within easy walking distance, kid friendly, putt-putt boat hire for explorers, berthing for your yacht, and tennis on a spectacularly located and historic court that should be included in the Grand Slam! Oh for the toffs and well funded, and no doubt cheap at the price, Heritage houses, the Superintendent’s villa with sweeping veranda views $600 midweek ($900 at weekends) or the former residences of senior officials, now two duplex Harbour view apartments, with large balconies, between $370 and $470 per night. But whatever your financial station, with minimal use of Shank’s Pony (the feet), the million dollar views are only a few steps away. for everyone, and they are all for free.

I started at the bottom level and climbed the steps (there is a ramp approach) up to the convict precinct, now a beautiful buttery sandstone ruin, which caresses the sunlight, but then indeed a grim pestilential prison, which the convicts first had to construct under the watchful eye of the Redcoats with their Brown Bess and Pattern 1842 rifles, build their own isolation cells as well as soldier’s barracks and a loophole guardhouse, with the iron hammock hooks still in the walls. Then too, there were the overseers’ cottages to build.

Cell block steps down to the isolation cells

Mess Hall for Convicts

Parade ground and Sunderland Dock

Guardhouse

Guardhouse interior

The early days of the colony were beset by fears of “food security” given the need to grow crops as the supplies brought out from England dwindled. “Northern hemisphere seeds” often failed in Australia’s harsh climate. Governor Gipps, who in 1839 was responsible for the utilisation of Cockatoo Island as a place for convicts and ship repair, also had convicts hew massive “silos” from the sandstone, for the storage of grain. While the silos did indeed act as a suitable storage facility, convicts went down to scour the walls of the then totally enclosed silos, and were overcome by grain fumes. Some were rescued by roped-up and lowered brave fellow convicts, but there were deaths, resulting in “bad publicity,” more from nearby traders and merchants who believed that the island should take their food supplies from them rather than concerns about convicts. The convict life was not a happy one and some were to make sure it wasn’t so, for the silos soon fell into disuse. Now, they are a roosting place for assorted birds, a room with a view from their buttery-coloured rookery.

Convict silo

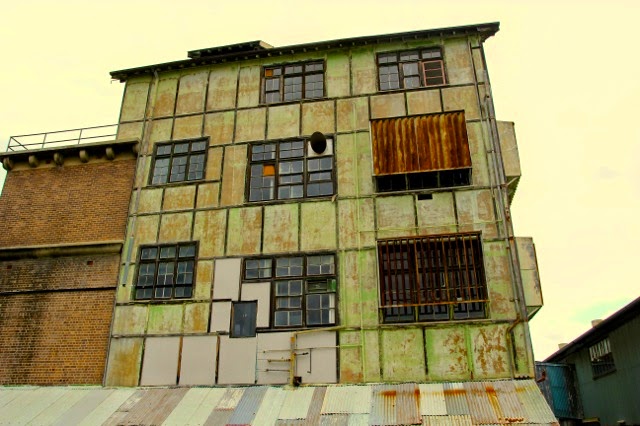

Beyond the “convict district,” the 20th Century industrial domain starts with all manner of equipment housed in huge corrugated iron sheds; a mould making loft so the projected ship could be laid out in timber template, first the bow section, then the stern and the requisite moulds made. There were drawing offaces, pattern design and polishing shops, electrical design workshops, carpentry and joining workshops, a timber drying store.

And all housed in sheds and stores which are now an orchestrated assembly of corrugated iron and rust, silent reminders from a time when they thrummed full of noise and movement, the buzz of saws, the pounding of iron presses, the smell of oil, diesels and grease, mingling with food smells brought in lunch boxes by men (and some women) in shirts, braces and ties, dungarees and overalls. The hiss of steam, the rumble of cranes on rails, the grunting and swearing of men at effort, wrestling with heavy equipment, waiting for the hoot known instantly to all, smoko, lunch break, or the much awaited ‘knock off time.’ Then there would be a rush to the ferries and the journey home to nearby cottages, often by way of the pub. Men carrying their Gladstone bags and invariably hatted, many still with the grime of their labours on them. That first Resch’s beer or Tooth’s ale would hardly touch the sides. All the talk of Bradman tand cricket or the Rugby League, depending on the season, the pub a lively heartland with shouts, calls, and fliirting with the barmaids.

Beam bending machine

The high point, with the sweeping harbour views, was of course for the island “gov’nor and the toffs,” and in later years, places for senior administrators and military men, a wonderful eyrie, way from the noise and the proletariat, with harbour breezes and city views. Biloela House is now full of artworks and serves as a conference hospitality venue. Even today, the sites are protected by particularly vicious seagulls reminiscent of Alfred Hitchcock’s famous movie scene in The Birds. A scull-numbing strike was my reward for foolhardily ignoring a warning sign that the sea-gulls were vicious and if I return again, it will not be without a tennis racket … to improve my back-swing! On my way to the tennis court, of course. And later, for a fetching a Pimms and Dry Ginger on the verandah would be just the shot before heading back to my accommodation (below).

I spent a few moments in reflection, looking down on the site below, the industrial machine sheds and open foreground where small hulls would have been laid, goods landed and sorted. In the war years, when American and Australian war-damaged ships were repaired and refitted, and in the post war period when ship-building was at its zenith, it was indeed the hive of industry. The Queen Elizabeth and the Queen Mary, some of the largest ships of their time, were refitted out as troop ships at Cockatoo Island.

Two tunnels run under the upper part of the island to make for easy connections to the main Sutherland and Fitzroy docks and in one a major first-aid post was carved into the rock after the 1942 entry of three midget submarines into Sydney Harbour, when it was feared the Japanese might attack the island from the water. As a major naval facility, a searchlight tower and a flak gun were also placed on the island as an aircraft from a Japanese mother-submarine had earlier dropped a couple of bombs on the nearby industrial city of Newcastle. With the torpedo attacks in the harbour (which sank a ferry and killed a dozen sleeping sailors), there was widespread panic in Sydney, although probably exacerbated more by the cruiser USS Chicago, firing its main armament at point blank range at “water targets” and the shells bouncing straight over some of Sydney’s most salubrious suburbs, and out to sea.

Looking to Sydney

Down below are the forges and foundries, where the heavy equipment, lathes and stampers, generators and turbines, mostly supplied after a long and arduous sea journey from England around the Cape of Good Hope, cranes towed for weeks by tugs that often lost their tow in mountainous seas. Now the sheds stand idle and empty, although historical societies are busy with restorative work to give some idea of their former glory. Some of them have been used for “rave parties” and also as location sites for movies such as Wolverine and Angelina Jolie’s new film, Unbroken. There remains the lingering smell of diesel and machine oils and it is easy to imagine the whirr and rumble of large overhead gantries, like spiders with steel legs clasping big bits of metal. Now it is all silent and largely bare, some industrial detritus left behind like droppings, signs that once these now rusted and shop-soiled ‘bits’ had been integral to what this place once was, and the work that was done. A time when the navy ruled the waves… but the unions ruled the shop floor.

I wandered back outside into the clouded sunshine and the rusted cranes that once were the work-horses of the dockyard, wandering the wharves on their set paths like grey flamingoes, picking things up, putting things down in all manner of vessels that plied the waters, items from holds appearing like landed fish, or disappearing into empty ships’ bellies. The Oberon class submarines were refitted at Cockatoo Island, a rolling program that took up to two years per ship, and the supply ship, the HMAS Success, was the last ‘big one’ launched there in 1984. In 1992 the Dockyard was closed and the much diminished ship construction industry moved to other states, as a politico-economic sop to political “vote buying."

The cranes like sentinels still stand, as testament to those earlier times when iron and steel were power personified, like Titan (above) and a host of others which from the water approach, look like industrial steeples that gave generations of Australians both work and the added security of being protected by steel grey ships.

There was time for a quick Bratwurst and sauerkraut at the cafe run out of a legendary Airstream caravan cafe, but like much of Cockatoo Island, it was closed, albeit only till the weekend when the crowds would come and the air will be full of the noise of children and yachties, the tang of sausages and salt on the breeze, birds wheeling overhead, that seagull symphony that no maritime movie is without.

I looked up as the white marauders wheeled above me. Once pecked, twice shy. I took the tunnel back to the ferry wharf, relieved that shrieking, shitting, sniping sea-gulls, would be denied a target. Now just a casual saunter to the wharf and then the bliss of bobbing home in a boat.

Winfred Peppinck is the Tales of the Traveling Editor for Wandering Educators

All photos courtesy and copyright Winfred Peppinck