The approximate 6,000 ships that have succumbed to raging storms attest to the power of the Great Lakes. As I traveled, writing and compiling information for my three-volume travel series, Exploring Michigan's Sunrise Coasts, Upper Peninsula Coasts, and Sunset Coasts, I heard or read the tales left behind by those ill-fated ships. They add a somber, but compelling backdrop to Michigan’s waterways.

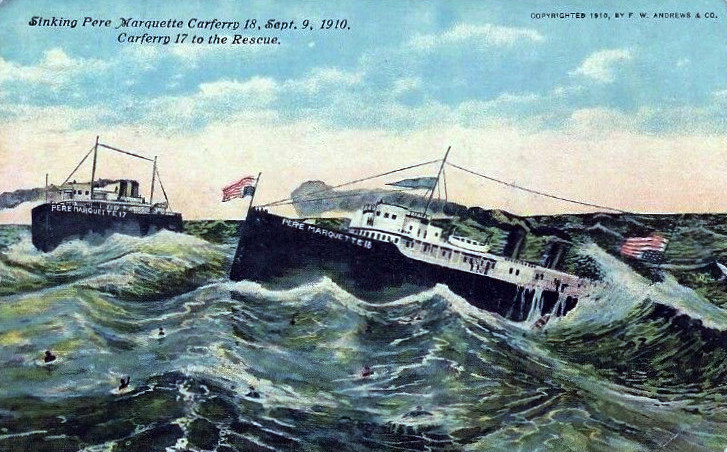

The ferry Pere Marquette 18 before she sank. Photo published sometime before 1910.

On September 9, 1910, the railroad car ferry Pere Marquette No. 18 took 29 passengers and crew to the bottom of Lake Michigan. The remaining 33 passengers managed to escape.

What caused the Pere Marquette to sink remains a mystery. She was not victim to a vicious storm, and although the waves were high, it is not likely they caused her to go down. She was not overcrowded, and to all appearances, she was in excellent condition. We might know more if Captain Peter Kilty had survived. He and all of his officers went down with the ship.

The Pere Marquette No. 18 was riding low in the water, and at some point, she was steering with difficulty. Seven feet of water was discovered in the stern, and water was pouring into the ship through portholes that may have been broken by the punishing waves. Twenty-nine rail cars were pushed overboard to lighten her load. The captain ordered his ship due west at full steam hoping to hit shoal water near Sheboygan in time to avert disaster.

During this drama, the captain also sent what may have been the first ship-to-shore radio distress signal in history. “No. 18 is sinking in mid-lake, for God’s sake, send help.” That terse plea, sent at 5:20 a.m., saved the 33 survivors who would otherwise have perished.

The Pere Marquette No. 17 responded to the distress signal and maneuvered around the side of the stricken steamer to be in position to take additional people aboard when the Pere Marquette No. 18 sank without warning. The bow bucked high in the air, and the ship slid stern first into the great sea. As it sank, there was an explosion that may have killed many of those still aboard. Fortunately, the Pere Marquette 17 was able to assist some passengers floundering in the water.

Postcard depiction of the sinking of the Pere Marquette car ferry number 18 on September 10, 1910. Copyright 1910 by F. W. Andrews & Co; card was mailed December 1, 1919

After that first wireless message was received, seven additional messages were dispatched describing, for the first time, the horror of a ship going down as it was happening. The message above and the first two that follow came from the Pere Marquette 18, the remainder from the Pere Marquette 17, as she responded to offer assistance:

“No. 18, sinking between Ludington and Milwaukee, for God’s sake save us.” (5:20 a.m., the same time as the original message.)

“Help, quick, Carferry 18 is sinking.” (5:20 a.m.)

“Steamer 18 went down.” (From Pere Marquette 17 at 7:30 a.m.)

“Steamer 18 is gone. No 17 standing by. Will stay until all are saved.” (7:35 a.m.)

“Frank Young, James Fray, and Cochrane were saved. All officers of No. 18 lost. Not one saved.” (9:00 a.m.)

“We have picked up 30 of crew of 18.” (11:00 a.m., and it was actually crew [no officers] and passengers.)

“33 lives saved altogether. We picked up five bodies. Captain Kilty, Purser Sczypank, Mrs. Turner, Cummings, and one unknown. Bodies on board No. 17 to be taken to Ludington at 4:00 p.m.” (1:00 p.m.)

In the aftermath of the tragedy, passengers who were saved described the efforts of the Pere Marquette 18 crew and accorded them the highest praise for their actions under harrowing conditions. According to survivor Seymore Cochrane of Chicago, he was reading a magazine in his berth when he heard shouts that the boat was sinking. He wrestled a door from its hinges and floated on it until he was picked up more than an hour later by No. 17. Later, in an interview, Cochrane said, “There is no other way of reasoning than to say the crew sacrificed their lives to save the passengers. The boat was well-equipped with lifeboats, and if the members of the crew had not been chock full of manliness, they might have saved themselves and let the passengers perish. But, thank goodness, they were not that kind of men.”

The shipwreck was found in 2020.

Click through to read excerpts from Royce's three books exploring Michigan's coasts:

Julie Albrecht Royce, the Michigan Editor for Wandering Educators recently published a three-book travel series exploring Michigan’s coastlines. Nearly two decades ago, she published two traditional travel books, but found they were quickly outdated. This most recent project focuses on providing travelers with interesting background for the places they plan to visit. Royce has published two novels: Ardent Spirit, historical fiction inspired by the true story of Odawa-French Fur Trader, Magdelaine La Framboise, and PILZ, a legal thriller which drew on her experiences as a First Assistant Attorney General for the State of Michigan. She has written magazine and newspaper articles, and had several short stories included in anthologies. All books available on Amazon.

Help promote Michigan. Books available on Amazon.

All photos in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons