Excerpted from Rambles into Sacred Realms: Journeys in Pen & Paint, by Krish V. Krishnan

Spread out like a crescent, the ghats of Varanasi lend an ethereal view to this sacred place. Just like the bustling temples that reside upon them, ghats have their own legends. From the limpid waters of Assi Ghat, where the goddess Durga had once thrown her sword down after destroying demons, to the murky waters of Varana, nearly a hundred ghats skirt the bank of the Ganges.

Pehlwan and the Sadhu

Acrylic on hardboard, 16 x 20

During the two weeks I spent in this land of contradictions, I was an object of curiosity to many a sadhu (holy man) who watched me as I wandered the ghats making my sketches — not a common sight in this part of the world. Some of them overawed me with their appearances and appurtenances, and when they congregated as a group, I felt an element of fear. One of them, known simply as Maharaj, had ashes smeared all over his body, sported matted locks, and carried a skull and trident, the insignias of the god Shiva. Another smoked a tobacco pipe and often laughingly threatened to open a basket that housed, as he put it, one of the most poisonous cobras in India; once he did open the basket, and I shrank away. They often poked fun at me and offered me questionable food. To them this unusual city slicker offered immense entertainment.

One day in the late afternoon, I was expected to arrive at the ashram where my parents were performing the anniversary ritual for my grandfather. I blundered from one ghat to the other until I had wandered hopelessly far away from my destination. It had become ominously cloudy, and a downpour seemed inevitable. For a fleeting moment the sun straggled through a cloud bank, lighting up the water and silhouetting the mottle of boats ahead. Dhobis (washermen) were hurriedly pulling clothes from makeshift strings.

Unmindful of the impending downpour, a glistening pehlwan (bodybuilder) was effortlessly wielding a stone mace. Just at that moment Maharaj walked by in the foreground, calm and collected. Clad in ocher robes with smeared ashes all over him, he added an elemental contrast to the scene.

I had to capture this and did a quick pastel drawing on gray paper, a clever way to capture nature’s changing moods. I eventually recreated the scene on hardboard painted white, using acrylic with some pointillism and dry-brush technique I found effective.

One evening I watched the evening riverbank aarti (worship with lights) at Dasashwamedha Ghat (page 60). Mythology runs that Brahma, the god of creation, once performed a sacrifice here to celebrate Shiva’s advent to the planet. One of the oldest ghats in Varanasi, dating to thousands of years ago, it is also the holiest, teeming with sadhus and pilgrims lost in prayer and worship.

The poet Tulsidas composed his verses of the Hindu epic Ramayana while meditating at Tulsi Ghat. The tall pyres of Harischandra Ghat cannot be missed, and legend has it that King Harischandra, the practitioner of inviolable truth, once worked in the crematorium here, the gods testing his devotion to virtue. In the burning pyres of Manikarnika Ghat, the flames rise up, hungrily consuming mortal bodies, ensuring moksha (liberation) for the deceased, and legend also tells us that when Shiva was performing his dreadful dance of destruction here, a bead from his earring fell into the waters.

In this city of seemingly countless temples, I didn’t know where to begin. Yet the thousands of tourists who spill out of buses onto the winding streets of Benares seem to have a clear mission. Many come out of curiosity to see where their forefathers may have trodden hundreds of years ago, risking the perils of forests, brigands, and wild animals in quest of salvation or monkhood. Some come here to perform last rites for their dear departed, firm in their conviction that there would otherwise be no rebirth. Many pilgrims arrive during the festive months when the stars and planets align into auspicious combinations, and like during the Kumbh Mela festival, the ghats burst into color and the air is filled with unsuppressed chants of devotion.

In the busy lanes of Viswanatha Gali lies the temple of Kasi Viswanatha, venerated as the guardian of the world.

“This shrine is the most visited spot in this city,” Raju, my auto-rickshaw driver and self-styled guide, explained earlier in my visit.

Wracked by centuries of pillage but rebuilt by the queen Ahilyabai Holkar in the late eighteenth century, this golden temple is not easily visible from the streets. Trying to get there, I accidentally ended up at the interesting mosque of Gyanvapi (right), which has Hindu pillars on the back, the front being a typical stucco structure.

This was the original seat of the older Viswanatha temple when the iconoclastic emperor Aurangzeb destroyed the shrine, even as a protective priest plunged into the well with the stone sivalinga. The emperor chose to not plaster the ornate pillars with stucco as a testament to his conquest over the Hindu faith.

Integration Inconceivable: Gyanvapi Mosque

Scratchboard, 12 x 16

Sepia wash, 12 x 16

Pen and ink, 16 x 20

The contradiction was startling — here was an inconceivable integration of faiths. Huge minarets and white domes in the front disguised the remains of an ancient temple behind.

A ruthless Muslim emperor had razed an ancient temple to the ground and intentionally left these walls intact as a reminder of his intolerant might over other beliefs. In a fit of rage, he raided the temple’s sanctum and hurled the sivalinga (stone shaft symbolizing Shiva) into the Gyan Vapi, the Well of Knowledge.

As I walked along the grounds, I saw a few cows lazing around under the blazing afternoon sun, unmindful of the gory events this place must have witnessed three hundred years ago.

I made an elaborate pen drawing of this scene in about forty-five minutes.

A sepia wash with ink highlights seemed to be the best way to capture the softness of this scene. The past seemed long forgotten in the search for a new age of peace.

I later recreated this scene on a scratchboard to enable me to capture more details of the intricately carved walls of a temple long gone.

The Gyanvapi mosque abuts the abode of the god-king of Varanasi. Unlike at most of the elaborate temples, space here comes at a premium, and very quickly I was inside the sanctum where the idol is housed. An oblong black stone, the Lord of Kasi is worshiped here as a jyotirlinga (symbol of effulgent light).

“Varanasi is known as the City of Light for yet another reason,” Ramdev Shastri had told me. Countless years ago, when Brahma and Vishnu were contemplating the true nature of God, a blinding beam of light from below the netherworlds split the ground asunder, flaring an endless way up to the heavens. This was the essence of godhood without any earthly attributes.” He then recited a Sanskrit verse and continued: “The place where this happened is right here; it was in holy Benares.”

The Temple Heist

Scratchboard, 8 x 10

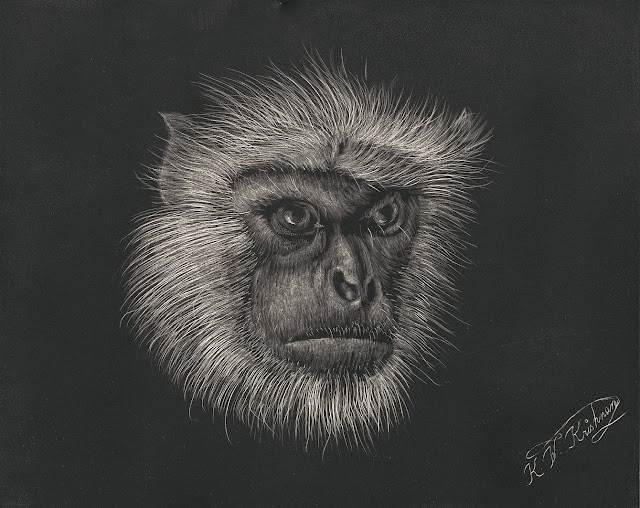

The rhesus monkeys, or what I simply call temple monkeys, are a frequent sight in these parts of the world. However, the Hanuman langur is probably less common in urban areas of Varanasi. Named after the Hindu monkey-god Hanuman, these primates are treated with some reverence.

It was evening in the Cowrie Mata temple, where pilgrims offer the traditional goodbye to Shiva’s sister before departing the city. As I was climbing the steps, I heard a ruckus somewhere above the rocks. A hungry mother langur had made away with someone’s lunch of Indian bread and curry rice and was bounding up the rocks, her baby in tow. A woman screamed at her simian adversary, waving her hands menacingly.

A male langur watched this scene from a ledge above. As the sun slanted on his face, lighting up his white tuft, I could see him studying the woman with great intensity, ready to make a protective move if any harm was to befall his family.

I used scratchboard to capture his sharp features and the wispy white tuft of hair.

Very soon, it was all over as the langur troops moved on to forage another shrine, and the temple monkeys finally took over.

A short walk away is the shrine of Annapurna, Shiva’s consort in her role as the provider of food aplenty. Her image sits majestically on a throne; in one hand is a ladle with which she generously doles out food contained in a vessel she holds with the other. She doesn’t sit far from another well-known temple dedicated to Durga, a more fearsome form of the Hindu goddess. It is perched on a hillock, and I had to pass several troops of bold monkeys to get to the sanctum. The goddess is seated upon her leonine mount, her hands holding symbolic insignia, one of which grants eternal protection.

Later in the evening I hurried along the lanes into the Viswanatha shrine. Chants resonated from within the sanctum where priests, representing the Seven Sages of Hindu mythology, were performing worship.

Oblations innumerable were being offered to the hallowed stone: milk, honey, flower garlands, and platefuls of sweets, fruits, and nuts. As camphor flames blazed high and incense filled the sanctum with wispy smoke, prayers rose to a crescendo.

No sooner did this worship conclude than pilgrims rushed in for a last glimpse of their divine protector before he retired to rest at midnight. But within hours he would be up again, awakened from cosmic slumber by priests in prayer. The Lord of Kasi never gets to rest; he needs to be ever vigilant so he can watch over the great city he rules and the people he protects within it. Not just the living but also the dead, who would continue to reside in the heavens forever.

About Krish V. Krishnan

Consumed by a deep-rooted passion for exploring exotic cultures, author, artist, and traveler Krish V. Krishnan has visited over 60 countries and lived in several, publishing more than five hundred articles on travel and humor in various newspapers all over the world.

Krish won a Best Travel Writer of the Year award and also received accolades for raising from obscurity previously little-known places through his writings and artwork.

He captures the essence of places by using a variety of techniques including scratchboards, watercolors, and acrylic mediums. He has held several exhibitions worldwide and is a member of a number of prestigious artists’ organizations.

When not holding a pen, brush, or an airplane ticket, Krish heads up a global corporation, shifting gears between Thai, Hindi, Thinglish, Hinglish and English. An alumnus of the Harvard Business School, he lives in Wilmette, Illinois, with his wife and daughter, continuing to coax his recently graduated son to embark on a study-abroad experience.

His upcoming book Rambles into Sacred Realms: Journeys in Pen and Paint features 12 destinations around the world each set in a different country, and is accompanied by over 100 pieces of artwork executed in a variety of mediums. The book is slated for release on April 6, 2015.

Learn more: kvkrishnan.com