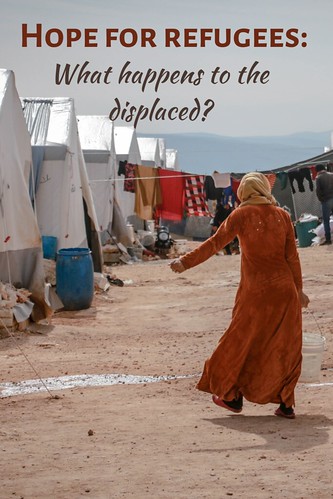

Hope for Refugees: Saved but not Safe

Here is a story about a 15-year-old boy called Rifat living in the city of Aleppo in Syria in 2016. Since 2011, Syria has been in a civil war, and the residents of Aleppo, like all Syrians, were living with the effects of the war. Rifat’s parents tried their very best to protect Rifat, his three sisters (aged 9, 15, and 16), and a brother, aged 13, from feeling the effects of the violence surrounding them.

They were determined to keep the family together at all costs. Almost all boys of Rifat’s age had been forced into joining the various armed groups involved in the war, but his parents knew the psychological effects suffered by child soldiers, and they hoped to protect their children from participating in the war.

Unfortunately, Rifat’s parents were found out, and the family resorted to his parents’ last option: smuggling Rifat across the Turkish border. Rifat’s uncle took responsibility, and arranged his journey out of Aleppo. Rifat is now a refugee in the United Kingdom.

Although he is currently safe, Rifat wishes that he could pull out his family from that situation and protect his brother from the hell he passed through to get into the UK. He is unable to, because you cannot bring any family member into the UK as an unaccompanied child refugee. He does not know the whereabouts of his family members—and does not know if they even survived the war.

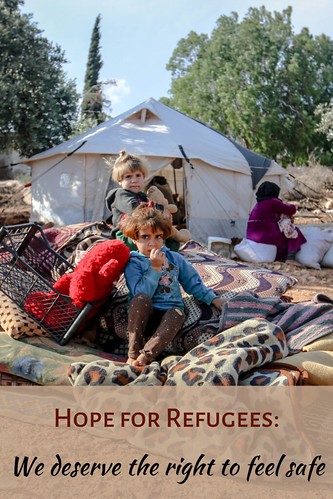

This story is quite sad. However, it is a reality that thousands of children who flee dangerous situations (such as wars and conflicts) and seek refuge find themselves alone in other countries.

Some travel alone, while some begin the journey with a family member—but along the way, they become separated. Before getting to their destinations, many of these children are exposed to death, abuse, starvation, and other terrifying conditions—and they will live with these traumas for the rest of their lives.

Global statistics on UASC (Unaccompanied and Separated Children)

The United Nations Refugee agency, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), has reported that children make up about 40% of the total number of the world’s displaced persons, and there are around 153,300 cases of unaccompanied and separated children worldwide.

Ethiopia is home to the world's largest number of unaccompanied and separated children, with more than 41,000 unaccompanied and separated children seeking refuge in Ethiopia.

In Europe, UNICEF reported that between January to June 2020, Germany had the record for the highest number of child asylum applications with 25,755 children, followed by France (9,590 children), Greece (8,385 children), Spain (8,115 children), and the United Kingdom (3,445 children).

However, the number has increased post-covid-19 pandemic. The Refugee Council reported that in the year ending June 2022, the UK received 4,896 applications for asylum from unaccompanied children. These children come from war-ravaged countries like Sudan, Syria, Iran, Albania, Afghanistan, and many more. Although the UK is willing to act as a sanctuary to these children and offer them shelter, they are unwilling to offer the same to the families of the separated child.

The effect of UK policy on reuniting families of refugees

The UK is the only country among its neighbors that refuses to grant child refugees the right to be united with their families—and this refusal is contrary to the UK’s international obligation, as a State Party to the United Nations Convention on the Right of the Child (UNCRC).

Article 3(1) reads:

In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

Article 6(2) states

States Parties shall ensure to the maximum extent possible the survival and development of the child.

Article 9 (1) states

Parties shall ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents against their will, except when competent authorities subject to judicial review determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child. Such determination may be necessary in a particular case such as one involving abuse or neglect of the child by the parents, or one where the parents are living separately, and a decision must be made as to the child’s place of residence.

Article 10 (1) states

In accordance with the obligation of States Parties under Article 9, paragraph 1, applications by a child or his or her parents to enter or leave a State Party for the purpose of family reunification shall be dealt with by States Parties in a positive, humane and expeditious manner. States Parties shall further ensure that the submission of such a request shall entail no adverse consequences for the applicants and for the members of their family.

From the provisions of the UNCRC stated above, the best interest of a child is to reunite with the child’s family—but the UK policy that prohibits a child refugee to family reunion is in clear contravention of the child’s best interest, and thus is in breach of the child’s human rights.

What happens to these children in the UK?

Upon arrival into the UK, unaccompanied and separated children usually become the ward of the nearest local authority. Recently, the Home Office made a directive to all local authorities with children’s services to provide care placements for them as part of the New Plan for Immigration. This directive aims to provide unaccompanied asylum-seeking children the much-needed care and end the use of hotels as temporary residence for them.

Before now, unaccompanied children upon arrival into the UK were kept in hotels. There were disturbing concerns about the poor level of welfare these children received while they were in these hotels, often neglected for months without adequate food, clothing, and health care. A result of this is that the children are left more traumatized and damaged than how they were when they arrived in the UK.

Another consequence of the lack of supervision and poor welfare is the number of children missing daily from these hotels.

Even with this recent directive of ensuring the local authorities share responsibilities of providing care to the children, their obligations are limited. Authorities are obliged to provide care for a child and to plan for their future, but they do not hold any parental obligations to the child. Thus, these children have no one taking charge of their everyday lives; there is no sort of legal guardianship.

Who then is responsible for the child’s much-needed mental and physical well-being, having been through so much already?

In addition to these disturbing reports, Refugee Council has warned that hundreds of child refugees are being hastily assessed as adults by the Home Office, and are at risk of being abused based on this assessment, such as sharing rooms with adults, the chances of being sent to Rwanda by the UK government to claim asylum there, and being denied welfare services, such as education and healthcare. The consequences of these wrongful assessments are massive and have the ability to adversely affect the child for the rest of his life.

There is also the fostering option; some children end up living with approved foster carers who provide the necessary parental care these children need for proper development. However, these fostering opportunities do not come by often, and when they come, the said foster parents have a long road ahead of them to deal with all the issues attached to caring for a traumatized child. It requires the utmost of care and patience, bearing in mind that almost all the foster children might not be able to communicate in the English language. Nonetheless, many people, such as Zara, are willing to foster these children and share their peculiar experiences.

Without My Family Report

Refugee Council, Amnesty International, and about 49 other organizations have been actively campaigning for a change in the UK immigration system when it concerns the reunion of families. These organizations jointly produced a report titled Without my Family report: the impact of family separation on child refugees in the UK. Therein, they detailed the negative effects of a child separated from his family; the report gave very vivid descriptions on how these children feel without their families with them. The psychological effects of separation were enunciated. One kid described it as having a body without a soul.

According to the report, the reason the Home Office has refused to allow child refugees sponsor family members into the UK is to discourage criminals from using vulnerable children as a means of entering the UK illegally. The same report dismissed this line of argument to be unfounded and indefensible, based on the findings of other neighboring European countries.

The change we need

It is obvious that the Home Office cannot provide child refugees in the UK with the necessary care needed for their wellbeing and development. And assuming they do have enough human resources to adequately care for the unaccompanied children in their care, they are in breach and violation of the child’s human rights by denying the child access to his parents and siblings.

I hereby join the Families Together coalition in urging the UK government to:

* Allow child refugees in the UK the right to sponsor their close family, so they can rebuild their lives together and help them integrate in their new community.

* Expand who qualifies as family, so that young people who have turned 18 and elderly parents can join their family in the UK.

* Reintroduce legal aid for refugee family reunion cases so people who have lost everything have the support they need to afford and navigate the complicated process of being reunited with their families.

Read more in this series:

Sandra Okafor is the Refugee and Forced Migrants human rights editor at Wandering Educators. She is currently studying a Master's in Human Rights and Diplomacy at the University of Stirling. She is motivated by the desire to impact knowledge and to empower others in creating a better world.