For the ancient Mayans, chocolate acted as currency. As a food for the gods. As a drink reserved for royalty and rituals.

Thanks to the Mayans, the rest of the world came to know the power – and appeal – of chocolate. It's a story that's told from start to chocolatey finish at the Ecoparque Museo del Chocolate (Eco Chocolate Museum) in Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula.

The museum stands across the street and in the shadow of Uxmal, an expansive stretch of Mayan ruins (which dates back to 700 A.D. and is thought to have 25,000 inhabitants). For many visitors, the most impressive remnant within Uxmal is the Pyramid of the Magician. Known for its unusual, distinctive and rounded edges the pyramid rises 115 feet into the air. (Uxmal lies an hour south of the more popular, and crowded, Chichén Itzá ruins.)

Uxmal Ruins

While venturing around the pyramid and the other ruins, I could hear the regular calls to the rain god Chaac, as part of a ritual reenacted at the nearby Chocolate Museum. Indeed, the museum weaves history, ecology and a bit of culinary mystique as part of what it offers to visitors.

Sign for Chocolate Museum

When we arrived we headed straight to the rain ritual. The 15-minute ceremony unrolls as men dressed in white tunics come from each direction – north, south, east and west – and call out to Chaac (incidentally, it did end up raining heavily the next day).

From there, we wended our way through the displays of how chocolate is made – from the palm-sized cacao pods to the cacao beans to a hot, liquid cocoa.

Signs along the way showed other plants with significance to the Mayans, like the achiote spice – the seeds have a bright, red color and a mildly spicy flavor (the spice that gives cochinita pibil its characteristic rosy hue).

Displays explain in detail how and why the Mayans used chocolate, although some of the information still remains conjecture. It's thought that the Mayans discovered cocoa 900 A.D. The Mayans found that if they opened the cacao pods, they could create a soothing, yet bitter drink from the roasted beans.

Chocolate Museum tasting area

The drink became shrouded in legend – and ritual. One museum placard explained the following:

The cosmogony of pre-Hispanic societies was founded on deep religious beliefs and natural phenomena. The ancient Maya believed that every night the sun had to unleash a ferocious battle with the beings of the Underworld, to rise once again in the morning, the victor, returning the light of the world. The Mayas gave offerings to the sun to strengthen it, offering human hearts as food, in this way assuring that life would continue. Many others gods also had to be fed with human blood, as human life was what maintained or changed the order of the cosmos. Due to this very close link between human beings and the natural cycles, human sacrifices were a common practice.

Many of these human sacrifices were volunteers. Fray Diego Duran (1537-1588), a Dominican Spanish priest and historian, recorded how one man drank several cups of cocoa mixed with water during a native celebration. The concentration of theobromine (a substance similar to caffeine, found in cocoa) put him into a trance, and he offered himself as a sacrifice.

Pyramid of the Magician

Cocoa became intertwined in many parts of Mayan life, from rituals to acting as a form of money among the various peoples.

When the Mayans were conquered by the Aztecs, they in turn continued using cocoa as a form of payment, and as a sought-after drink.

From there, it's believed that Christopher Columbus brought cacao beans back with him from the New World to the Old. But the beans' arrival went unheralded until another European explorer, the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes, realized the lure of the "bitter drink." Cortes is credited with declaring chocolate in 1519 – "The divine drink which builds up resistance and fights fatigue. A cup of this previous drink permits a man to walk for a whole day without food."

I couldn't agree more.

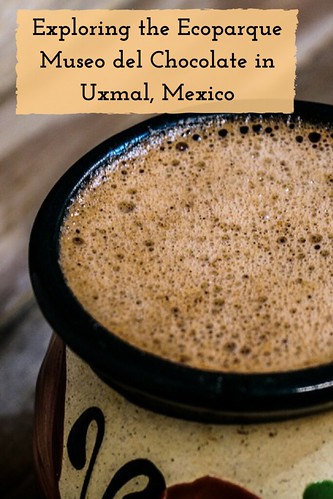

The culmination of the museum's various exhibits (which also includes displays of local wildlife) is a demonstration where guides show you exactly how the hot cocoa drink is made from pod to bean to drink. And yes, visitors are offered a steaming cup. You can take your pick among ingredients to mix in, like chile, sugar, and cinnamon.

Pot of hot chocolate

I mixed a sprinkling of sugar into my first cup. And for the second? I stirred in a bit of cinnamon.

Visiting the chocolate museum is a fully immersive experience – offering a mix of sites, sounds and tastes of an ancient world that's still impacting our modern one.

Walkway to the Chocolate Museum

Click here for MORE chocolate museums around the world!

Kristen J. Gough is the Global Cuisines & Kids Editor for Wandering Educators.

Word photo courtesy creative commons. All other photos courtesy and copyright Kristen J. Gough